TL;DR: The BLS jobs report was quite good along nearly every dimension.

Key data points:

Unemployment rate: fell to 3.8% (good)

Prime working age employment population ratio: unchanged at 80.7% (decent)

Nonfarm payroll employment: rose by 303K (very good)

Wage growth: ~4.0% annualized over the past 3 months (near or a little above where the Fed wants it)

Topics I’ll cover in this recap:

The Big Picture

Don’t Be a Doomer About Part Time Work

Thoughts About Immigration

The Rise in Black Unemployment

1. The Big Picture

If I had to summarize the data over the past 6-12 months in 1 sentence, it’s:

A supply side boom has allowed for slight cooling in the labor market coupled with robust employment growth.

If allowed a second sentence, I’d add:

Maybe that cooling is over.

As Hillel the Elder famously said, “the rest is commentary.”

If you zoom out, a few things stand out:

The unemployment rate of 3.8% is a little higher than it was 12 months ago (3.5%), and unchanged from where it was 6 months ago.

The prime working age employment population ratio, at 80.7%, is unchanged from where it was 12 months ago and a little lower than it was 6 months ago (80.8%).

Wage growth has been 3.8%-4.1% annualized over the past 3 months, lower than 12 months ago (4.6%-5.1%) but a little higher than 6 months ago (3.7%-3.9%).

Key JOLTS “labor market heat” data like hiring and quit rates have declined over the past year.

Employment gains stopped moderating last summer and are still robust.

What’s allowed bullets (1)-(4) in tandem with (5): a supply side boom which includes is surges in business formation and (undercounted) immigration.

There are pessimists who argue that 5 is an erroneous artifact of BLS overcounting. I don’t find this to be very convincing, but even if they are correct, the first 2 bullets (and probably the 3rd and 4th) remain standing: the labor market has cooled a little, not a lot. Assuming increases in the unemployment rate continue at the pace of the past year, we’ll reach 4.5% in 2026 and 5.0% in 2028. Not sure what I would call such an unprecedented outcome, but it wouldn’t be “recession”.

It’s also quite possible the increases in the unemployment rate are done, and the current degree of cooling we’ve seen is “as cool as it will get” in the next few years. It depends on inflation cooperating enough for the Fed to put a floor under the labor market, which is my base case (my 2024 labor market preview).

2. Don’t Be a Doomer About Part Time Work

One pessimistic strain of discourse around the job data has emerged because of recent strength in part-time employment. For example, in March, the household survey indicated that overall employment increased by 498K. The increase in people who usually work part time (34 hours or less per week) was 535K; the number of people who usually work full time (more than 34 hours per week) actually decreased by 37K. IS THIS BAD?!??!?

The answer is mostly “no”. The BLS usefully splits part-time workers into those who are doing so “for economic reasons” and those who are doing so “for non-economic reasons”. Economic-reasons-driven part time work falls into two main buckets: “slack work or business conditions” or “could only find part time work”. And there are a wide range of reasons why someone might work part-time “for non-economic reasons”: they take care of a family member, they go to school, they have health reasons, or maybe they just feel like it.

"For economic reasons” usually accounts for a minority of the part time worker universe, and is a useful labor market barometer - it goes up when the labor market is bad, and goes down when the labor market is good. We’ve seen it go up a little bit over the past year, consistent with the mild cooling we’ve seen in other labor market metrics (discussed earlier in this recap).

But in March, “part time for economic reasons” actually decreased by 68K; the increase in part time came from those doing it “for non-economic reasons”. And that type of part-time work tends to go up when times are good. Why? Because strong labor markets give people options - whether they want to work longer hours, or shorter ones.

I don’t know why we’ve seen a big surge of people working part time for non-economic reasons over the past 6-12 months, but I doubt it’s because of a worsening in the labor market.

3. Thoughts About Immigration

As stated earlier, I think there’s some evidence that we’re undercounting migration and that this is affecting data in the jobs report, but I nevertheless took a peek at the data on immigrants we do have.

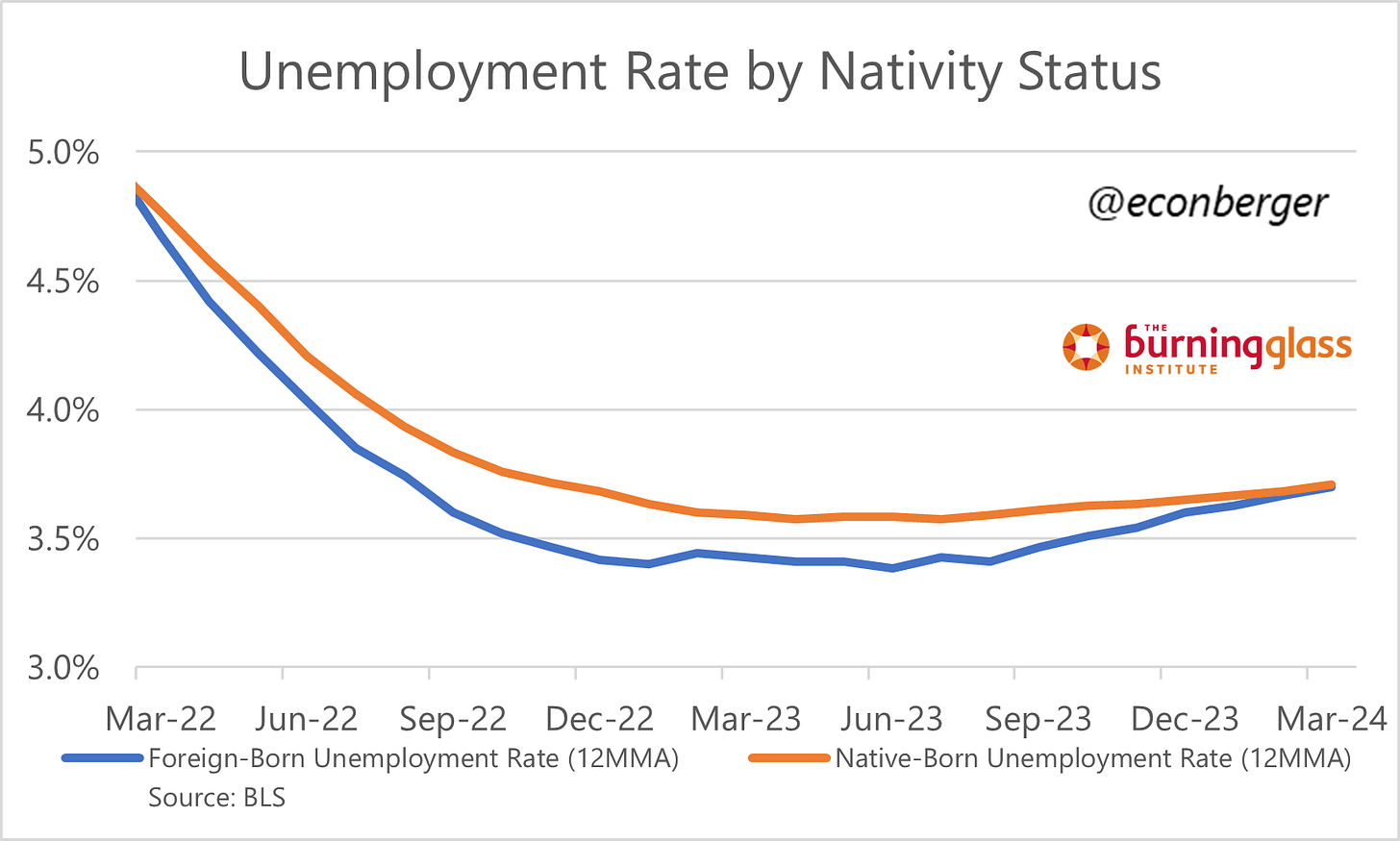

For most of the past 2 years, immigrants have had a lower unemployment rate than the native-born. That gap began to narrow sharply last year and has now disappeared.

The unemployment rate has increased a little over the past 9 months, as discussed earlier, and we can decompose that increase between native-born and immigrants. Immigrants have experienced a much larger increase, but are a smaller group, than native-born, so they account for roughly 40% of the (small) increase.

Now imagine that the BLS is, in fact, undercounting immigrants in the household survey, and that the undercounted are behaving in a similar way to the actually-counted (unclear). That would mean the orange bars would be bigger. Another way of thinking about it: the increase in the unemployment rate might be larger than the BLS currently estimates, due to an immigrant undercount.

4. The Rise in Black Unemployment

I don’t have a lot to say about this, but one of the few bad data points in the report was a sharp increase in the black unemployment rate. That’s the highest it’s been in 2 years. Folks tend to worry about this kind of thing for two reasons - first and foremost, it’s bad for black people; second, it’s a possible leading indicator of weakness elsewhere.

I think some worry here is appropriate, but not too much. Small household survey subsamples are notorious for generating high frequency, meaningless noise. Is there any good explanation for the ephemeral bump in Hispanic/Latino unemployment a year ago, or for the dip in Hispanic unemployment this month?

On the other hand, we have plenty of other evidence that the labor market has cooled a little over the past 6-12 months, and it would unfortunately be historically typical for Black and Hispanic Americans to feel that worse than White Americans.