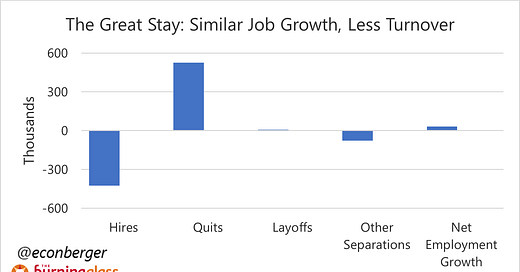

TL;DR: The “Great Stay” continued in February, with hiring, quits and layoffs all below normal. Relative to a year ago, job growth has increased a little but turnover is down substantially.

In the rest of this recap, I’ll cover:

The Great Stay Continued

Job Growth vs. Turnover

Uggh, Openings

More below chart:

1. The Great Stay Continued

I came into this year anticipating that the Fed would put a floor beneath hiring and quits, allowing them to stabilize. This may be happening, but it’s really too early to tell.

The “Great Stay” continued in February. Hiring, quits and layoffs all remained below where you would expect with an unemployment rate of 3.9%.

The hiring rate ticked up to 3.7%. Historically this would be consistent with an unemployment rate of just under 5%. Or stated differently, you’d expect more people to be starting jobs given the currently low unemployment rate.

The quit rate has been unchanged at 2.2% since late fall. Historically this would be consistent with an unemployment rate a little above 4%. (So quits are unusually low, but less unusually than hires.)

Quits have been less noisy than hires, so this is probably the most stabilization-consistent data point. A few more months and I’ll be ready to declare “I’m vindicated”.

And layoffs increased a little, to their highest level since July. Despite all the panicky headlines about layoffs, this level matches the pre-pandemic record low. And like hiring and quits, layoffs are lower than you would expect with an unemployment of 3.7%.

I don’t really have an answer to the question of whether these low gross flows will “normalize”. All we know from the past 3 years is that flow volume is not a deterministic function of measured labor market slack.

2. Job Growth vs. Turnover

I’m not surprised hiring and quits are a lot lower than they were a year ago. But I am surprised that this happened with limited impact on net employment growth. In fact, if you look at the most recent 3 month period and compare it to the same 3 month period a year ago, net employment growth has actually increased a little!

I’m not sure what to make of this, though I have some weakly-held hypotheses. In descending order of how much I believe them:

Supply side: We have lots of evidence that, along with other blockages on the economy’s supply side, a lot of previously unavailable labor is now available. Immigrants are one important example! We’re used to hire and quit rates coming down because of weaker demand, but they could easily come down because of stronger labor supply. An employee is less likely to leave their existing because of heavier competition for a fixed set of outside opportunities; that leads to their existing firm not needing to hire a replacement. The timing fits, too. If this is correct, it could continue until the labor supply boom plays out.

Bullwhip: One argument that I’ve heard from folks like Conor Sen is this is a “bullwhip effect”. Employers are fine with the current pace of headcount growth, but think it is more fruitful to grow/develop/invest in employees they overhired in 2021-22 than to lay them off and hire new ones. This is a nice complement to other things we see in the economy (for example, faster productivity growth) and, if true, will probably peter out within the next few years.

Labor hoarding: we’re using to talking about “labor hoarding” (fewer hires, fewer layoffs) in the context of this labor market, though even here there’s a twist. It’s one thing to say “employers are afraid to lay off workers during a period of temporarily lower demand, so instead they’re dialing back on hiring”. But the steady growth of net employment seems to suggest this more about a headcount growth strategy than about a temporary headcount cap. Perhaps this is just a variant on 2.

Employers actually want to cut back, but are failing: A pessimistic take is “out-of-equilibrium behavior” - employers are trying to cut back on hires, but their employees refuse to quit, so at some point layoffs will tick up, pushing down net employment growth down as well. I don’t find this to be convincing - if true, I would have expected some movement in layoffs over the past year, and we just don’t see any. (Indeed, over the preceding year, 2021-22 to 2022-23, we simultaneously saw a decline in net employment growth and an increase in layoffs.)

Mix shifts: Our population is getting older. That means, over time, less job switching. Additionally, existing workers have stronger track records, which makes layoffs less appealing. It explains why turnover is lower than 10-20 years ago, but doesn’t do much to explain what’s happened over the past year. Another option here that I haven’t investigated is inter-industry shifts - basically, job growth is shifting from high turnover industries to low turnover industries; probably the biggest counterargument is that a lot of the industries dominating recent job growth are industries with higher-than-average turnover! But I’m open to someone digging in further on this.

3. Uggh, Openings

As you know, I am not a fan of the job openings data (despite being a JOLTS fanatic). They’re significantly exaggerating how hot the job market is. (I think it’s “warm” a la 2017-18, but not hot.)

On a shorter frequency, they do seem to suggest we may be stabilizing - they’ve been flat recently after a period of steep decline.