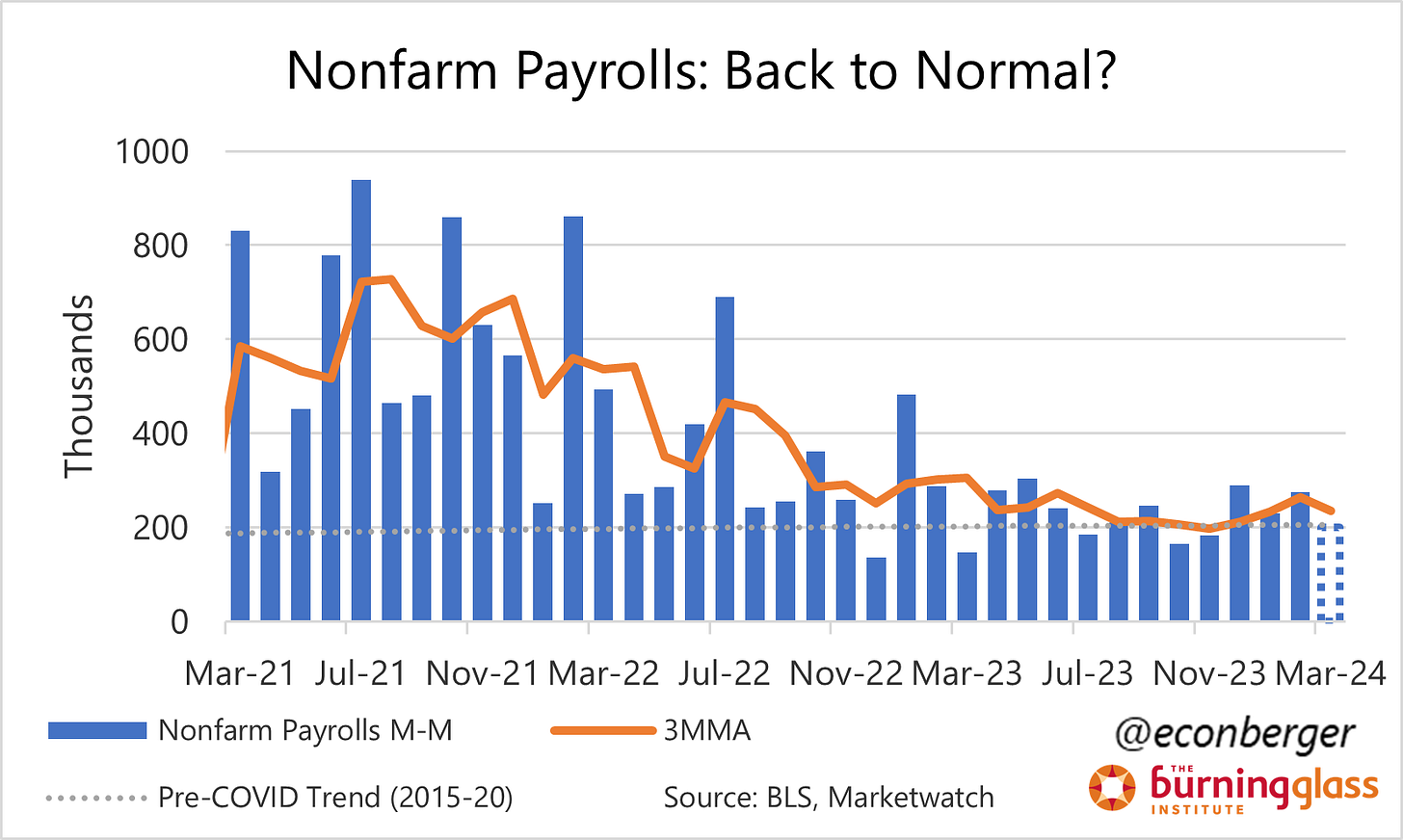

TL;DR: March is expected as another solid month of labor market gains, with an increase of 200K in nonfarm payroll employment and a moderation in the unemployment rate to 3.8%.

In this preview, I’ll discuss:

The big picture

Reconciling the Household and Establishment Surveys

1. The Big Picture

The US job market continues to expand and is not on the verge of recession. There is some ambiguity over the pace of expansion - some indicators like nonfarm payroll employment look very robust, whereas the unemployment rate is very gradually creeping upward - but nothing I’m alarmed about. I’m hoping to see clearer signs of stabilization (that was my prediction for 2024), but haven’t seen them yet.

Beyond that core theme, two worries I’d had in recent months - one “too cold”, another “too hot” - have dissipated.

On the “too cold” side, I was a little worried a few months ago about was the share of prime working age Americans with a job: it peaked at 80.9% over the summer (the highest since 2001), then fell to as low as 80.4% in December… but rebounded to 80.7% in February. I don’t think we can distinguish “noise in a flat series” from “very slow and gradual decline” but even if you take the latter seriously, it implies a full percentage point decline every 3 years or so. That wouldn’t be great, but wouldn’t be alarming either.

On the “too hot” side, there was a pickup in wage growth, from a little below 4% during the summer to over 5% around year-end. IMHO the link between wage growth and consumer price inflation is too weak and loose to have much implication for the Fed’s ability to hit its 2% inflation target, but I’m not sure they see it that way. So it’s nice to see us wages growing around 4% again.

All in all, the current employment situation of not-very-hot wage growth and ongoing expansion is conducive for the ongoing but not-yet-complete soft landing.

2. Reconciling the Household and Establishment Surveys

As you’re probably sick of reading in this newsletter, the monthly BLS jobs report compiles data from two sources - the Current Population Survey (aka CPS or “Household Survey”) and the Current Employment Statistics (aka CES or “Establishment Survey”). And over the last 6-7 months, the two surveys have told very different stories.

A. The Starkest Chart

Let’s start with the starkest chart - since March 2023, the establishment survey has counted over 2.5 million jobs added, whereas the “concept adjusted” household survey has tallied under 0.5 million jobs added. That entire gap emerged in just 3 months. Is it possible that, as the concept-adjusted household survey employment count suggests, we turned a sharp corner after November and have shed 1.5 million jobs in the past 3 months?

I’m very sure the answer is no. The household survey is typically more useful in ratios like the unemployment rate and the prime-working-age employment ratio. The unemployment rate did go up by 0.2 percentage points over the past 3 months (not good), but the prime working age employment population ratio was unchanged (ok). There are reasonable interpretations of the ratio data that are mildly pessimistic (“slack in the labor market is slowly increasing”) but none that indicate “we’ve tipped into or are on the verge of tipping into recession”.

B. The Interim QCEW Numbers

A more nuanced and plausible version of this story is “no we’re not in a sudden and recent phase of large scale job losses, but we have good reason to believe that the establishment survey is steadily overcounting job growth”.

One supporting piece of evidence is the fact that the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), the source data for the BLS’s annual benchmark revision of the establishment survey, has recently run much weaker than the establishment survey itself (by about 900K since the most recent benchmark date, March 2023).

I don’t want to dismiss the QCEW entirely in this context, but the track record of intra-year QCEW metrics in predicting benchmark revisions is imperfect at best. The QCEW wiggles around a lot more than the CES! In the six months since the March 2023 benchmark, it ran colder than the CES, then slightly stronger, and now a lot colder.

What happened after the 2022 benchmark revision is also illustrative. QCEW data through September 2022 was running hotter than the CES, then took a turn for the worse, and we wrapped things up with a negative 2023 benchmark revision.

A wise BLS expert once summarized this as follows: it may very well be that the QCEW’s wiggles are reality, and the smoothness of the CES is fiction. But you cannot make inferences about the future from those wiggles. We have 6 months of QCEW data to come before the next CES benchmark estimate (we’ll have them in hand in August), and a lot can happen in the interim.

C. Business Formation

One of the stronger “establishment survey is correct” arguments anchors around US new business formation. Census data indicates this was incredibly strong during 2023. Employment at these new businesses is likely to be undercounted by the establishment survey sample (hence the robust net birth/death adjustment pessimists are grumbling about), though “team household survey” is reasonably in noting that the CPS shouldn’t have this problem.

To the degree that strengthening business formation has helped power strong employment growth in 2023… not sure how much of a repeat we’ll get in 2024. The level of new business formation is high, but no longer rising, in Q1 of this year.

D. Immigration

I’ll wrap up this piece with another fairly plausible explanation for the gap: the household survey is undercounting immigrants.

The household survey is anchored to Census Bureau population estimates that are updated once a year, then incorporated into the household survey. Most employment report readers encounter this process in the January jobs report, when they encounter this annual disclaimer:

The twist here is that the source data for the population controls is actually older than the “control date” - it’s as of mid-year the prior year. If there’s a sudden change in population growth behavior in the subsequent 6 months, despite predating the population control date, it won’t show up until a year later. (e.g. If population growth changes behavior in the 2nd half of 2023, we won’t see it in CPS data until early 2025.)

So it is certainly conceivable that population growth perked up in late 2023 and we don’t know it from the CPS data. Other sources, such as CBO, which look at the whole year, estimate a much heftier, immigration-driven population increase, as Wendy Edelberg and Tara Watson discuss here.

Anyway, we won’t resolve this for sure for quite some time (early 2025?), but I find the immigration and business formation data to be pretty persuasive.