Tech Innovation in Labor Market Matching

A Formerly Useful Sword Develops a 2nd Edge

This piece has a bunch of unempirical thoughts about how tech has affected the job application process, from an economist’s perspective. I’d love to learn what practitioners and job applicants think, or if you have data weighing on any of my speculation!

TL;DR: Unlike earlier technological innovations in labor markets, recent declines in job application costs may be harmful to both job seekers and employers.

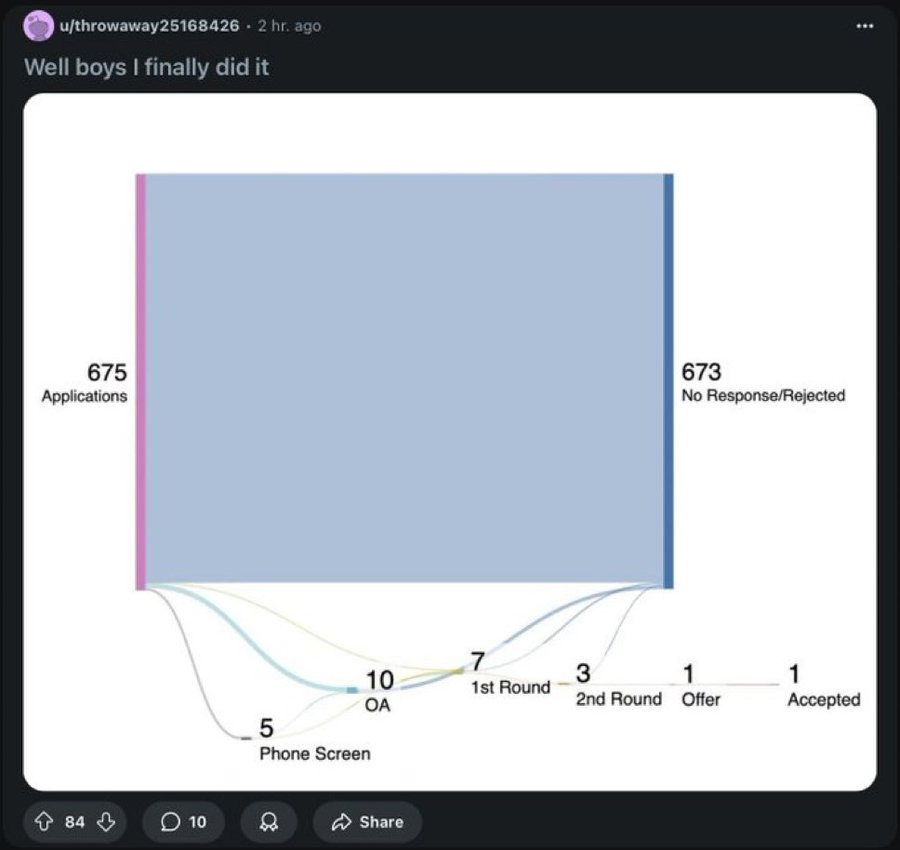

Screenshot from Reddit via Twitter

1. The First Wave of Tech Innovation in Online Job Markets Was Good…

It’s hard to imagine for many people under the age of 40, but a long time ago, you couldn’t use the internet to find a job. You relied on word of mouth, ads in the newspaper and broadcast media, industry-based matching, job fairs, recruiters, and probably a bunch of other channels I can’t remember due to advanced age.

This was a messy and time-consuming process. Information was very fragmented. There were lots of great candidates that hiring managers didn’t know about and had no way of reaching. There were lots of great opportunities that jobseekers didn’t know about, and had no way of discovering. Even if both parties knew about each other’s existence, they didn’t know each other’s status - whether they were both available for a match at the same time.

Throw sand in the gears of a market, and you’ll get worse outcomes. In all likelihood wages and profits were both lower on average, because of all those forgone great matches. I think you can probably make the case that aggregate employment was a little lower too. And both sides were just wasting a lot of resources (time, money) trying to find matches.

The internet radically changed this by defragmenting information. All of a sudden employers could find those great candidates they didn’t previously know about, and those jobseekers could discover all those great opportunities they didn’t previously know about. The existence of online public resumes and job openings meant that employment/vacancy status was less of a mystery.

This was a 2nd order, not 1st order, improvement in labor market outcomes. There was a common hope among participants in the online labor market tech space, especially in the awful early 2010s job market, that this would eliminate unemployment. It didn’t. The reason the job market improved as the 2010s went on is a boring cyclical one: the economy was growing and needed more workers, creating opportunities for workers who needed them.

But 2nd order improvements aren’t nothing! People found better jobs than they would have in the pre-labor-market-tech world; employers found better employees. Job search costs fell. And while the business cycle continues to be the primary driver of aggregate employment and unemployment, I’m reasonably confident that better and more efficient matching led to a slight improvement on this front too.

2. …The Second Wave of Tech Innovation, Less So

A. Job Application Gets Easier and Faster

Because of the information defragmentation process mentioned in the prior section, a lot (not all) of the pre-tech inefficiencies in the labor market were wrung out of the labor market by the late 2010s. But innovation didn’t stop. It’s gotten easier and easier to apply to online jobs - the amount of tedious form filling has diminished as various application platforms have gotten better at accurately absorbing information from resumes and online profiles; some platforms offer one-click “easy apply” features.

Extra time and energy spent on applications is time wasted that you could be spending with your family or friends, reading a book, binging on a TV show, or sleeping! So on its own, less effort seems like a good thing.

But imagine a world where actual job opportunities are relatively widely known and limited (which is the actual world we’re in, particularly since hiring is weak). There are only so many people that will get these opportunities. It’s ambiguous whether lowering the cost of applications is beneficial.

If the efficiency of the hiring process is unchanged with a higher volume of applicants, lowering application costs is probably positive on net. Some people who wouldn’t previously apply (because it uses time and energy) rationally conclude that even with a low probability of getting a job, it’s worth shooting their shot. Nothing wrong with that!

For relatively high quality and high urgency candidates - those who would apply anyway, even at a higher cost - lower application costs are a good thing because they’re spending less time on each application. They might improve their chances of finding a job because they can reallocate that freed-up time to filling more job applications, or finally catch up on Andor Season 2.

And for employers, the possibility that a high-quality candidate might be discouraged by a time-consuming application process is worth avoiding. As long as the screening and interview processes don’t see any degradation, it can’t hurt to have more applications!

But there’s probably a good chance that these processes are being degraded by more applications. More candidates without more job openings imply more aggressive screening. That can happen in the interview process itself (which is time/energy consuming), or it can happen earlier: rejecting more applications upfront. This rejection process can be manually done by humans (again, time/energy consuming) or by technology.

It used to be that screening technology was unsophisticated, and non-human filtering cut wheat as well as chaff.1 With AI’s growing abilities, I’m open to the possibility that it performs application review as well as or even better than humans.23 This is ultimately an empirical question, but I’m reasonably confident that the gap has narrowed in the past decade. (Though you should follow this footnote for a more skeptical perspective.4)

I’m not sure how these two sets of effects - degradation of the screening process vs. saving time and resources for applicants - predominates. But it’s at least possible that the former is larger; as I wrote earlier in this piece, throw sand in the gears of a market, and you’ll get worse outcomes.

B. AI-Generated Job Applications

LLM usage seems to be fairly high and rising, and that means more LLM-generated (or at least LLM-enhanced) applications. In other arenas, like education, this change has been at least somewhat disruptive because it makes it harder to evaluate the LLM user’s underlying abilities or effort. But I doubt it’s as problematic in the applications process.

If low-effort LLM usage creates a lot of predictable low-quality applications… those are probably easy to filter out? If it creates relatively high-quality applications, that’s not necessarily a problem unless your application process relies on high-effort responses (essays? math problems?) or relies excessively on rejecting typos. Where things might get a little dicey is the volume issue - if AI allows applicants to create a lot more applications than would otherwise be the case, that could compound the problems described in section (2A).

One other worry is that LLMs make it easier for candidates to lie or exaggerate on their resumes. I’m not sure how much stock I put in this concern; I don’t see why an LLM would be better at inventing fake experiences or education than an unaided human prevaricator. I’d love to see some evidence from this front.

While I’m mostly skeptical about LLMs disrupting job applications, there are other parts of the hiring funnel where it could cause problems: homework assignments or technical screens. I could also imagine video-generation technology eventually becoming good enough to fake remote interviews, though the bar here is pretty high.

C. How People Feel About It All

So far I’ve been discussing the impact of tech innovation on the efficiency of the application process. But I wouldn’t disregard how people feel about it. Let me give a stylized, cartoonish example where I made up all the numbers. Imagine that a jobseeker needs to spend 100 hours of applying for jobs in order to successfully land one role. In the old, pre-efficiency regime this would have required 2 hours per application, with a 2% yield per application and a 1% yield per hour. In the new, highly productive regime, this would require 10 minutes per application, with a 0.17% yield per application and a 1% yield for hour.

Which of these is better for the jobseeker? If you’re thinking purely in terms of time/effort consumed, they’re the same.5 But maybe jobseekers care a lot about avoiding tedious effort and are willing to take a lot of rejection (in which case the efficiency is good); or alternatively, they hate rejection and are willing to undertake a lot of tedious effort to avoid it. The amount of grumbling we see about applying hundreds or thousands of times suggests that people really hate rejection; but maybe “I spent all this time on 20 job applications and only heard back from 1” would be equally hated.

I don’t know which of these predominates and I’d be interested in finding out! Maybe some platform is experiencing with reintroducing frictions into the hiring process and has learned something interesting as a result.

I’m also interested in how people feel about greater dependence on algorithms in the application process. You sometimes read grumbles about how it’s harder for your resume or application to make it to an actual human being. People seem to dislike this, though I’m not sure they dislike it more than a world where you put in a lot of effort to produce fewer (but human-read) applications.

////

I hope this was an interesting speculation from an economist’s perspective - if you’re a practitioner or job seeker, I’d love to hear your feedback!

In weak labor markets when hiring managers were inundated with high quality candidates, this kind of sloppy screening might nevertheless have passed the cost/benefit bar relative to more time-intensive human review.

Don’t overrate how good human beings are at this kind of activity.

There’s a worry about discrimination and bias with both AI and humans.

At least one person who knows the specifics threw some cold water on this assessment. Kevin Virobik wrote:

“I think you might be over your skis here. Please name the AI screening tool that is broadly used within industry that provides your confidence.

Amy Miller and other well-known recruiters spend a lot of time debunking the "ATS rejected my application" myth. AI screening is one of those things that seem like they should have been broadly adopted, I am reasonably confident that the reality is that adoption has yet to near critical mass.

And while the case is heavily nuanced, the Workday age discrimination case likely will have many businesses reluctant to jump on board AI application review for the time being.”

Reminiscent of money illusion.

1. Have you thought about Glassdoor at all in this section? I have been pondering the "Glassdoor" effect on wages and company culture.

2. CVs and Resumes have been high error anyway. I do agree that optimizing this part of the jobs market may have gone so far as to add costs into the experience for both employers and prospective employees (recruits). I think this indicates more than anything the need for innovation through other parts of the market. Some examples:

- Streamlined recruitment that focuses on employee pools (recruiters should return back to the same applicants and have a process for picking preferred applicants in accordance with the employer's needs),

- Internships that are driven more by the college so that placement happens faster and for more students,

- talent development programs that drive employees and prospects to new opportunities (the amount of wasted talent is unreal and needs to be actively rooted out, since it is an opportunity cost sort of thing that will not show itself naturally),

- online testing for applicants and other reasonable requirements that edge out the easy appliers (make applicants do just enough work to show they aren't just hitting the "Easy Apply" button),

- and more responsive NOs from the employer which gives applicants clarity on when they're not being considered or have been passed on (the most insufferable thing is to be in the purgatory of having a bunch of applications sent out to employers and no responses, not even rejections).

As an unemployed economist, I have thoughts.

It is Jevons paradox, as we made something easier, more people use it, and the worse everything gets.

Everyone must now play a game to get hired, to get the perfect ats resume, to bypass the recruiter and try to network with the hiring manager.

The Chinese have a word for this, involuted. It is excessive, often self-defeating, competition and effort to gain a slight advantage, leading to diminishing returns and a sense of futility.

We made life hard for no reason at all and just acccept this is how things will be from now on.