Jobless Claims: 'Tis the Season(al Adjustment Confusion)

What is unemployment insurance data telling us about unemployment?

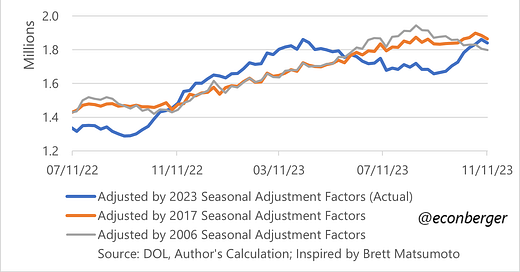

TL;DR: Continuing claims for unemployment insurance, historically a useful proxy for unemployment, are probably exaggerating the recent deterioration in the labor market due to funky seasonal adjustment.

The rest of this post discusses:

What are continuing claims and why are they a useful data series?

Why is seasonal adjustment causing problems with this data, and how can we correct for it?

More below chart.

1. What are continuing claims?

Every week, the Department of Labor’s Employment & Training Administration (ETA)1 publishes a report in which they tally up state-level data on unemployment insurance (UI). This report contains a lot of interesting data, but two of the most closely followed are initial claims and continuing claims for UI.

Initial claims are, as you can guess, the first time an unemployed person files for unemployment insurance. They are often used as a proxy for layoffs, since people can only receive UI after losing your job (i.e. if you voluntarily quit or retire, you can’t get UI).2

Continuing claims3 are any subsequent UI filing after the initial claim. They’re often used as a proxy for the number of unemployed people (though technically speaking, they’re only a subset of it - people who quit their job or enter the labor force aren’t getting UI). This linkage makes conceptual sense: for the BLS’s Current Population Survey, to qualify as unemployed you usually need to fulfill the criteria “don’t have a job” and “actively looking for work”; those are necessary (but not sufficient) conditions for receiving UI.

The UI claims data is useful because it’s published earlier than the monthly BLS jobs report. For example, the next jobs report, coming out on December 8th 2023, corresponds to the state of the labor market during the week of November 12th-18th. But we’ll already have in hand initial claims data from the week of November 26th-December 2nd, and continuing claims from the week of November 19th-25th. The BLS data is the gold standard, but the claims data is a useful nowcast.

One final point - the first is that initial and continuing claims data is seasonally adjusted. If you look at the raw data, you see a predictable, recurring pattern of a big claims spike right after the winter holidays, and also a smaller but still large spike in the early summer. Seasonal adjustment is a statistical process that flattens out these predictable wiggles and allows us to extract the underlying trend in the times series. It also allows us to do informative comparisons over frequencies different than a year.

2. Why is seasonal adjustment causing problems with this data, and how can we correct for it?

Starting in early fall 2023, after about 4 months of gliding slowly downward, continuing claims surged. From September 23rd through November 4th, they rose from 1.67 million to 1.86 million - the highest level since December 2021. An increase of over 10% during a short period is nothing to sneeze at, and during a period when folks are already on edge about the state of the labor market, raised some concerns about the dreaded R word.

But take a careful look at that picture: the timing of the renewed ascent is identical to the one that began in 2022. From September 24th through November 5th of 2022, continuing claims rose from 1.30 million to 1.45 million (and kept on increasing to 1.86 million in April 2023 before declining).

Could the seasonal adjustment process be malfunctioning, introducing some predictable noise into the officially published data? Is the recent increase indicative of a sudden deterioration in the labor market, or is it actually echoing a deterioration that is far into the rear view mirror?

One option we have is to look at alternate seasonal adjustment factors - for instance those from 2017, which had an identical calendar to 2023. Using these alternates results in a different story - no predictable zig zags, but rather a steady deterioration from November 2022 through at least August 2023 (no spring improvement), and a slower increase over the past 2-3 months.

How much do we believe that alternate story? On the plus side, the seeming residual seasonality apparent in the official seasonal adjustment factors is gone. It’s just a less volatile trajectory, and fits a fairly straightforward story of gradual labor market cooling. Nonfarm payroll employment also has a sort of gradual cooling over the past 12-15 months that may have leveled out recently.

On the minus side… well, first, seasonal patterns do change over time and the 2017 seasonal adjustment factors would miss that. Second, I worry because the Current Population Survey (CPS) is reporting a recent deterioration in both the unemployment rate and prime working age population ratio over the last few months. Those may also be the result of funky seasonal adjustment, or it could be that they’re confirming the official continuing claims story. We’ll have a better idea in a few months.

Where I land on this is that the recent sharp ascent in continuing claims (as well as the decline we saw in the spring and summer) is probably an illusion, and partly/mostly a seasonally-induced echo of increases that actually happened months ago.

Realistically, most of us aren’t going to muck around with alternate seasonal adjustment factors, and so it’s worth thinking about what the officially published data is going to look like in the next 6 months.

If we’re going to experience the same steady deterioration going forward as we did for much of the past year, we’ll track the grey line below - continuing claims will continue to zoom upward at least through early spring. The orange, more optimistic scenario is where we actually flatten out in “real” terms relative to last May. So far, we’ve been tracking somewhere in the middle - some ongoing deterioration, but less than over the past year.

Acknowledgments: Parker Ross is one of the first people to highlight that the improvement in claims over the spring and summer of 2023 was probably a quirk of poor seasonal adjustment. Brett Matsumoto proposed the “fix” of 2017 seasonal adjustment factors. Thanks to both of them for inspiring my thinking on this topic.

*Not* the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The ETA is a different subsection of the Labor Department!

Though pedantically, anyone can file for UI - even someone who quit or still has a job. They just can’t receive UI.

Officially, the name is “continued claims”, but for some reason “continuing claims” is also a commonly-used term and that’s how I learned it. So I still use it that way. Another term you sometimes see is “covered unemployment” - i.e., unemployment that is covered by UI.