A shorter than usual preview of Thursday’s jobs report, as I’m still on vacation!

TL;DR: After an extended period of stability, the labor market is likely to confirm renewed cooling in the June jobs report.

Sections of this post:

The Big Picture

Payroll Breakevens Have Fallen!

More below charts.

1. The Big Picture

Last July, the unemployment rose to 4.22%.1 At the time it seemed to suggest an acceleration in labor market deterioration - but in fact, was the beginning of a stabilization period. It wasn’t just that the unemployment rate stopped rising; hiring stopped declining in the JOLTS report, and quits leveled out soon thereafter. The prime working age employment/population ratio has puttered around 80.5% since the fall.

That pattern of relative stability across key indicators continued through mid-spring. But I suspect that we’re going to identify May or June as a turning point in the wrong direction. We’ve seen a small acceleration in continuing claims over this period; this is usually a useful proxy for unemployment due to permanent layoffs, the most cyclically sensitive component of unemployment.

The base case should still be a relatively small deterioration in the labor market. So far the acceleration in continuing claims is quite small. Things are moving in the wrong direction, but very slowly. The Fed anticipates the unemployment rate won’t go higher than 4.5%, and (conditional on what inflation does) would probably start easing policy if it showed signs of going higher. But they’ve also telegraphed that they’re going to be very data-reactive (instead of anticipatory), and there’s always the risk of small and gradual labor market deteriorations turning into big and disorderly ones.

2. Payroll Breakevens Have Fallen!

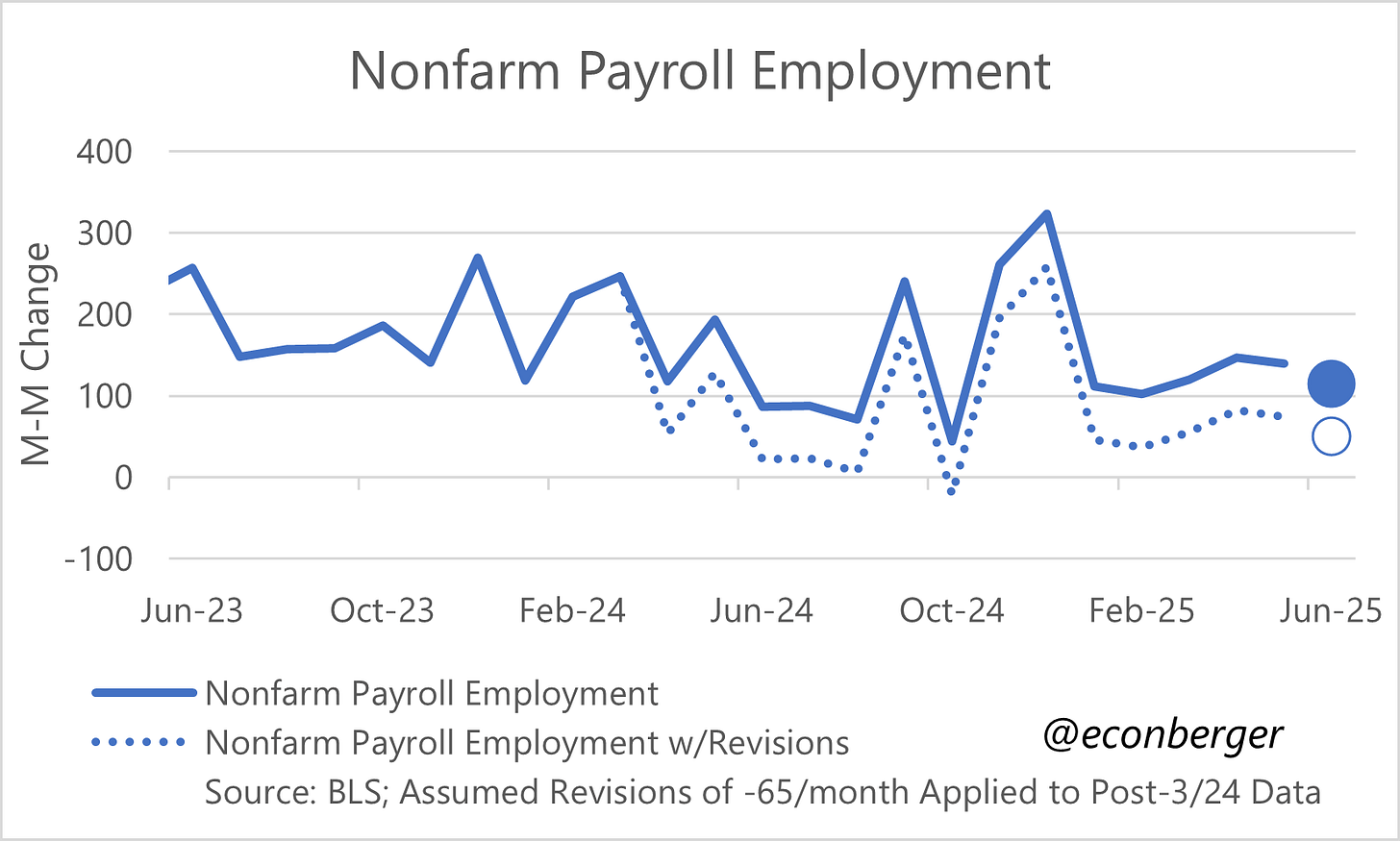

In the first 5 months of both 2024 and 2025, the unemployment rate rose by about 0.2 percentage points each time. But employment growth was quite different in each period. Currently published estimates are for average gains in nonfarm payroll employment of 180K/month in that 5 month period of 2024, and 124K/month in that 5 month period of 2025; if we take probable future revisions into account, the gap is even bigger: 154K and 59K.

The main takeaway is that the breakeven pace for employment growth has fallen a lot over the past year due to slower labor supply growth. We don’t need large monthly gains to keep the unemployment rate steady.2 A secondary takeaway is that, from the perspective of labor market cooling and tightness, future revisions to currently published payroll employment growth don’t matter. The unemployment rate, not vulnerable to big revisions, “did what it did” - discovering payroll growth was lower than we thought won’t change our perspective on “the labor market cooled/warmed”.

The payroll employment gains/losses each month are typically reported without this lens, but I strongly urge you to apply it. A lot of the reported cooling in employment gains in the past year (which will appear even starker after future revisions) will have no impact on how hot-or-not the labor market is.

If you want to read much more thorough analysis of the falling breakeven, I strongly urge you to read Jed Kolko’s much more detailed work.

To be pedantic, the number was a tiny bit different than that, due to subsequent seasonal adjustment factor revisions.

In fact, if labor supply growth turns sufficiently negative, then we might have a labor market steady state with negative employment growth.