BLS Job Report Recap (November)

Back on track (or maybe we stayed on track the whole time?)

TL;DR: November’s jobs report was good with almost no soft spots.

Key data points:

Unemployment rate: fell to 3.7% from 3.9% (good)

Prime working age employment population ratio: rose to 80.7% to 80.6% (good)

Nonfarm payroll employment: rose by 199K (good)

Wage growth: 3.4-4.2% annualized over the past 3 months (meh, from the Fed’s perspective)

Below I’ll discuss:

The big picture

Key data and nuance

Miscellaneous data of interest

1. The Big Picture

If you were bored enough to read my preview of this job report, you know I was looking for reconciliation of two dissonant narratives apparent in the US labor market data:

The job market was cooling until early this year, but has since stabilized

The job market is still cooling, and the cooling may have even intensified recently

I was hoping that the November jobs report would resolve this narrative, preferably in favor of narrative 1. That’s exactly what happened!

Since the spring, nonfarm payroll employment has been growing around 200,000 per month - not slowing down, not accelerating, and not very different from the pre-COVID trend. November’s employment report didn’t shift that trend.

What did shift was the previously-weak half of the report: the household survey. Key indicators like the unemployment rate and prime working age employment population all partly reversed some of their recent (very mild) deterioration.

This stabilization buys monetary policymakers time. The job market doesn’t look like it’s suddenly tipping toward recession, and also doesn’t seem to be reaccelerating. So the Fed can wait to see how the data evolves instead of making hasty decisions like hiking too late or hiking too soon.

I don’t think this means “higher for longer”, as some folks have concluded.1 Instead I’m thinking of something that Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller said last week:

“[If the decline in inflation continues] for several more months ... three months, four months, five months ... we could start lowering the policy rate just because inflation is lower… It has nothing to do with trying to save the economy. It is consistent with every policy rule. There is no reason to say we will keep it really high."

Over the 3-5 months (in time for the March FOMC meeting?) inflation could improve enough for a policy rate cut. It also might not.2 But this report is very well-aligned with Governor Waller’s easing bias.

I’ll wrap up this up by noting the mild fly in the ointment, wage growth. If the next few months of wage growth data replicate the strength we saw in November, yeah, I think that could slow Waller’s roll. But we’ve had plenty of ephemeral wage growth spikes in the last 2 years and I expect this month was no different.

2. Key Data and Nuance

2a. Nonfarm Payroll Employment

Nonfarm payroll employment grew by 199K in November. That’s remarkably close to the 3 month moving average of 204K, and also to the pre-COVID trend. Since April the 3 month average has just bounced around between 169K and 238K. This indicator is really stable, with little or no deterioration since the spring.

I’ve seen three “things aren’t as good as they seem” complaints directed at this upbeat picture, which I rank in descending order of plausibility as follows:

What about future revisions?

What about the narrowness/concentration of the gains?

What about the strikes?

What about future revisions?

In my opinion this is the most plausible challenge to the stabilization thesis. Downward monthly revisions to the April-September data have averaged 41K per month. Applying that to the October and November data points would land the November 3 month moving average at 184K, a little weaker (but still pretty solid).

That said, I’m not sure we’re due for ongoing downward revisions. These are historically associated with a negative 2nd derivative in employment growth, as Martha Gimbel has noted. But if we really are stabilizing, maybe those negative revisions will wind down. (Crossing my fingers.)

It’s also worth mentioning that adjusting the household survey’s employment concept to match nonfarm payrolls (from the establishment survey) suggests that nonfarm payrolls are undercounting job growth. Maybe the bias to future revisions lies slightly to the upside!

What about the narrowness/concentration of the gains?

Almost all of the employment gains in November came from 3 sectors: health care & social assistance (+93K), government (+49K), and leisure & hospitality (+40K). There’s an old metaphor I’ll borrow from Larry Summers, about the global economy flying with only one functioning engine - does that apply to the current US labor market? Is that 3 sector engine putting the labor market expansion at risk?

I doubt it. This kind of fragility story makes sense in situations where the growing sectors are susceptible to some sort of exogenous shock - such credit tightening for construction, energy price declines in mining, or a collapse of asset prices in a financially levered sector. None of that seems to apply to any of these 3 (with the possible/partial exception of government) - it’s hard to imagine any of them retrenching without an already-materializing recession as the trigger.

Additionally, both government and leisure & hospitality have so far trailed the recovery seen in overall employment; their growth has room to run.

What about the strikes?

This is the most lukewarm “cold water” that you can throw at the payroll numbers.

Nonfarm employment got a hand this month from the end of two strikes - SAG-AFTRA and UAW, accounting for around 40K workers. (There are probably also second order effects from non-striking businesses that had to cut back temporarily because of the strikes.) So it’s true, you can calculate an “excluding strikes” employment gain that looks less impressive.

But if you’re going to go that route, you also need to add offsetting strength to prior recent months’ gains, when the strikes began. And the end result of that calculation will be the same conclusion as before: using 3 month averages, employment is growing by around 200K a month.

2b. The Unemployment Rate & Prime-Working-Age Employment Population Ratio

I mostly covered this part of the report earlier - the household survey rebounded a little after a period of softness.

The unemployment rate fell to 3.7% from 3.9%, a four month low but a little higher than the 3.4% cyclical low reached earlier this year. 3.7% is an extremely low level by historical standards.

The prime working age employment/population ratio - which I think is a better measure of labor market “slack” than the unemployment rate - rose to 80.7% from 80.6%. It’s just shy of the post-2001 high we reached a few months ago (80.9%).

These measures are telling us that simplistically projecting recent declines forward into a semi-recessionary glide downward is probably a bad near-term forecast. But candidly, it’s hard to distinguish “neither improving nor worsening” from either “improving very slightly, very slowly” or “deteriorating very slightly, very slowly”.

One final aside - a month ago Skanda Amarnath (Employ America) and I were kicking around the possibility that seasonal adjustment of these indicators is having some problems, largely on the basis that a year ago we had a “weak fall / strong winter & spring” in both that seemed untethered from economic fundamentals, and it seems like the first half of that is repeating a year later.

I'm not sure there is, and I don't expect the forward trajectory will match last year's strength, but...

2c. Wage Growth

Average hourly earnings, our most timely indicator of wage growth, showed heat in November - it was the strongest single month of wage gains since July. On an annualized month-over-month basis, wages increased by 4.3% for all workers and 5.2% for non-managerial workers. On a 3 month basis, those numbers were 3.4% and 4.2%, which is a little warmer than the two years leading to the pandemic (3.0% and 3.3%) but much cooler than a year ago (4.6% and 5.0%).

Is there risk of wage growth heating up, and if so does that put possible Fed easing at risk? Well, we’ve had periodic ephemeral spikes in wage growth over the past 2 years, so I’m doubtful this one will stick.

But even if it fades and we return to the 3-month annualized figures of October (3.0% and 3.4%), I’m not sure we’re going to have much additional wage deceleration. It could be we’re entering a happy steady state for the labor market, with moderate wage growth and ongoing employment increases.

I’ll also observe that the causal link from wage growth to inflation isn’t that strong. Where consumer price inflation goes, up or down, will matter a lot more to the Fed’s decision than what wage growth does.

3. Miscellaneous Indicators I Look At

OK, let’s go around the horn and look at a bunch of interesting things I found in today’s report.

3a. Part Time for Economic Reasons: The cyclical part of underemployment - people who want to work full-time hours but can’t find enough work - which goes up when times are bad and goes down when times are good. Right now it’s very low by historical standards as a share of the workforce. A month ago it looked like it was very slightly deteriorating just like the rest of the household survey data, but that reversed in November.

3b. Average Weekly Hours: The average workweek ticked down a little last month but rebounded this month. Workweeks are still longer than they were pre-pandemic!

3c. Unemployment Due to Permanent Layoff: One of the few areas of the household survey data where we didn’t see improvement. This type of unemployment is about 1.0% of the workforce and has gone up by about 0.2 percentage points over the past year. It’s not getting worse, but I would like to see it getting better.

3d. Prime Working Age Labor Force Participation: Another area of the household survey that saw no improvement. It stayed at 83.3%, just a little bit below the post-2002 record attained a few months go (83.5%).

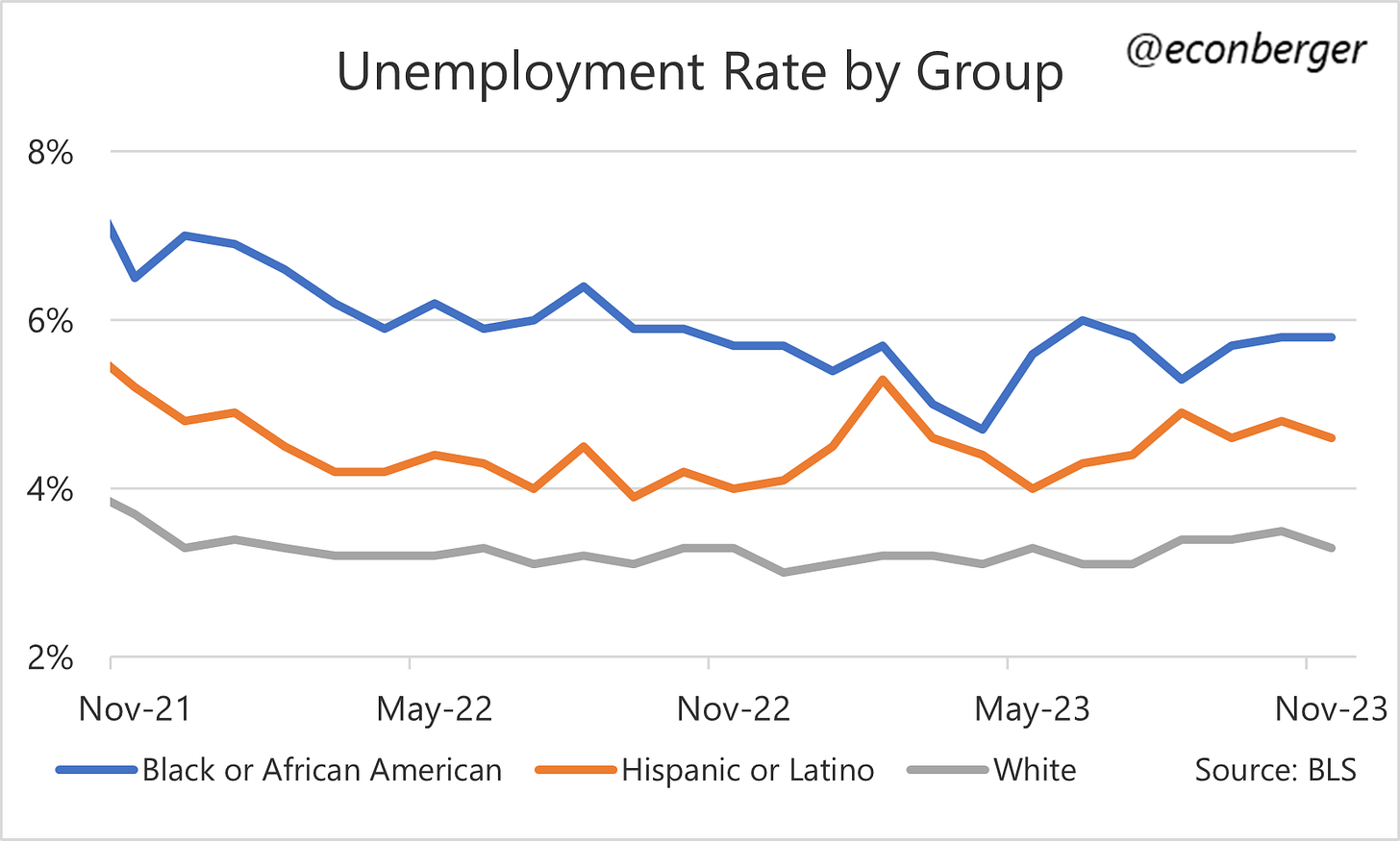

3e. Unemployment for Hispanic/Latino and African Americans: The unemployment rate for Hispanic/Latino Americans declined in lockstep with the overall population, but unfortunately African Americans didn’t follow suit - their unemployment rate was unchanged.

3f. Temp Agency Employment: Historically this was viewed as a leading indicator of the business cycle, but it’s been declining with only a few interruptions since last spring and recession has not come.

3g. No White Collar Recession: Employment for workers with a BA or above is doing fine, though it’s not matching the boom for workers without a high school diploma. The weakest category is for workers with “some college” or an Associate’s Degree - I’d love some good explanations of this.

3h. Workers Missing Less Work Due to Illness: The BLS publishes data on how many workers are absent from work full- or part-time due to illness. What’s interesting is that wholesale absences from work due to illness have almost entirely normalized to their pre-pandemic frequency, but part-time absences remain quite elevated.

I’m using “higher for longer” pretty narrowly here - no rate cuts through most of 2024 and possibly beyond.

If you want deep thoughts on inflation besides “it could improve / it might not”, this probably isn’t the newsletter for you. I’m a labor market guy!