TL;DR: This piece is a reflection on how the China-US trade war ceasefire changes the economic outlook and what’s next.

This piece has 3 short sub-sections:

How the outlook changes

Leading indicators and the labor market

What’s next

1. How the Outlook Changes

On Monday, we got an ceasefire announcement on the US-China trade war. The important “win” from the US perspective is a massive reduction in tariffs imposed by the US on China - i.e., a partial reversal of an economic on-goal. Additionally, the retaliatory tariffs imposed by China are also being partly unwound. This reduction is temporary (90 days) while the two sides continue to negotiate, and tariff decisions have been extremely unpredictable over the past 3-4 months, but I’m going to assume that it sticks.

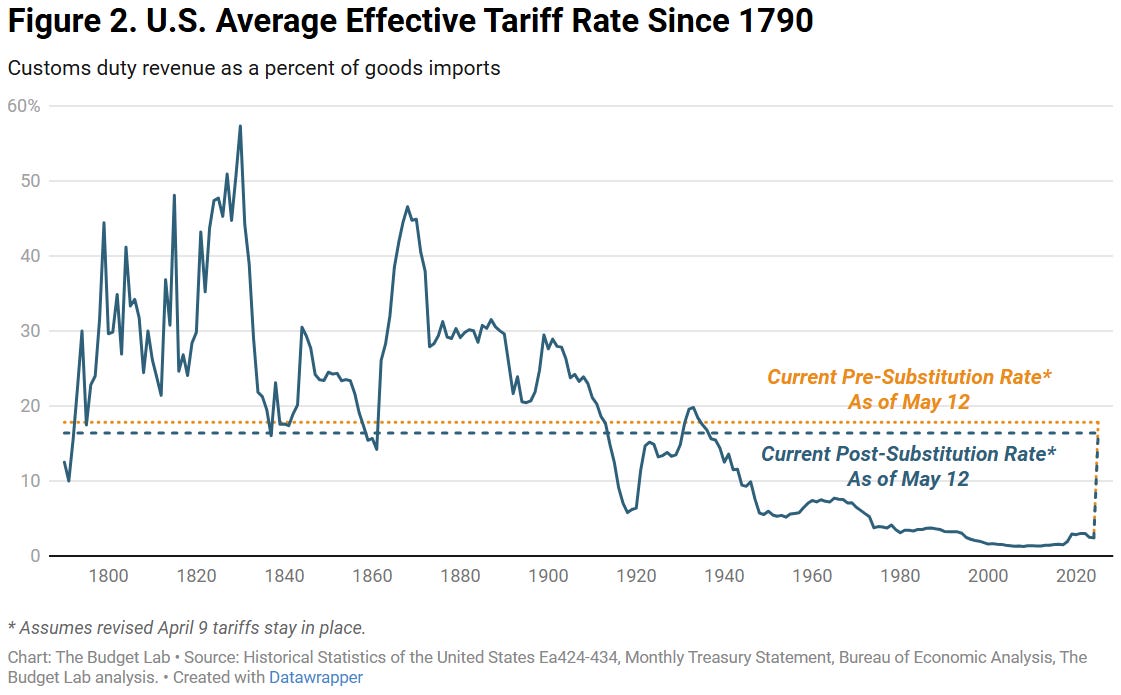

The main implication: an improvement in the economic outlook and labor market prospects relative to where we were a week ago. We should all be breathing a sigh of relief that things won’t be as bad as anticipated. But that’s not the only benchmark worth considering. The new, post-ceasefire tariff levels are higher than at any point since the 1930s. That means slower economic growth as the economy adjusts, and (holding all other policies constant) a weaker labor market in the short run.

I like analogies, so… if the original April 2nd tariffs were the equivalent of shooting yourself in both feet, the new tariffs are shooting yourself in only one foot, or if you’re really optimistic a few toes. We’re all glad to have one unharmed foot, but it’s better to have two.

As a labor market data watcher, I still plan to keep an eye out for emerging labor market softness, even if it will be less severe than previously anticipated. And I’ll also be looking for offsets from other policies to emerge over time (see section 3).

(I encourage everyone to read the Yale Budget Lab’s full report on the new tariffs.)

2. Leading Indicators and the Labor Market

Two things I hear a lot are the statement “the labor market is a lagging indicator” and the question “what are leading indicators for the labor market?” I think the last 6-8 weeks of headlines shed some interesting light on them.

Until the May 12th ceasefire with China, it was normal to talk about a gap between supposedly-abysmal “soft data” and supposedly-resilient “hard data”. I wrote a long piece about how this was the wrong frame, and instead we should think of a gap between weak “vibesy”/forward-looking soft data and mostly-resilient “current” data (both soft and hard). A reasonable assumption at the time was that the weak current data would eventually buckle, retroactively justifying weak expectations and vibes.

But with the ceasefire, the path for the labor market has improved - and all those weak expectations and vibes will probably represent an overshoot (and possibly overshoot in the opposite direction too, if there is excessive post-overshoot euphoria). Extreme worries were a form of cheap talk, and businesses that refused to radically change their employment behavior over the past month (almost all of them) have been vindicated. There are still good reasons to be pessimistic about the labor market outlook (see prior section), but any negative changes are likely to play out over an extended period of time rather than as a sudden stop.

This brings us back to leading and lagging indicators. Since I like analogies, we can think of layoffs as the top rung on a long ladder of increasingly-costly-to-reverse employer decisions when facing a weak economy. Before you get to that top labor market deterioration rung, you have to climb past intermediate rungs: termination of temporary employees, reductions in hours, and hiring freezes. Negative expectations and vibes are among the lowest ladder rungs. The lower rungs are “leading indicators” for the ones above them, in the sense that you usually have to climb past them. But they fail as true “leading indicators” for the higher rungs because many/most ladder-climbs don’t make it all the way to the top.

Anticipation of higher tariffs (along with the DOGE layoffs) began our climb up that labor market ladder; the April 2nd tariff announcement that kicked off the 2025 trade war in earnest generated expectations of a much faster climb, as well as greater confidence that we’d reach the top. But we hadn’t gotten past the lowest rungs before the May 12th ceasefire, and now the base case is a slower ascent that stops only partway up the ladder.

3. What’s Next

At the beginning of the year I wrote a fairly optimistic 2025 labor market outlook - the combination of large tax cuts, slower labor supply growth and an accommodative Fed would allow labor market stabilization, and possibly also labor market reheating. I considered and then dismissed downside risks like large government spending cuts and massive tariffs.

Events of the past three months shook my confidence in that upbeat outlook. But the DOGE cutbacks have been at a much smaller scale than I worried about 3 months ago, and now there seems to be a ceiling on the scale of the trade war. That brings into focus two other forces that could push the labor market pendulum, in the opposite, hotter direction: a big unfunded tax cut and lower labor supply growth.

The last 4 months have made me leery about drawing big conclusions about future economic policy out of the federal government. But unfortunately, I think we’re going to be whipsawing up and down that labor market deterioration ladder a lot over the next few years.

Hi Guy, thanks for the write-up. I'm wondering, do you recall your own or the 'common' sentiment towards the labour market around the GFC? Was there an expectation of a rapid deterioration in labour market conditions? How quickly did we move up the ladder?

Love the ladder analogy. Looks like we're going to get a workout climbing up and down those rungs for a while.