TL;DR: It’s too early for Fed easing to stabilize the labor market, so cooling probably continued through September (and probably will continue through early 2025).

In the rest of this preview, I cover:

The Big Picture

The Indicators

Some Things Are Different This Time

1. The Big Picture

The US labor market has steadily cooled in 2024 across a wide (but not quite unanimous) array of indicators. How much further will this process go?

We have two circuit breakers in the works, at least one of which will kick in before long. The first, and most discussed, is the Federal Reserve. The Fed reduced their policy rate 2 weeks ago (just after the reference period for this jobs report) and anticipates easing at least a little more (depending on how inflation and the labor market evolve).

Barring an unanticipated deterioration in the inflation data, the Fed will eventually succeed in stabilizing the labor market. They anticipate the unemployment rate averaging 4.4% in both Q4 2024 and Q4 2025. I think at least a small overshoot of this level is probable. My baseline is that the unemployment rate will peak between 4.5%-5.0%, and a peak above 5% is quite possible (let’s say a 15%-20% chance).

Note that my forecast doesn’t say anything about recession - we’re talking about the same gradual, non-recessionary cooling process we’ve experienced in the past 2.5 years. You can think of a recession as a subset of my “above 5% upside surprise” scenario - a situation where instead of gradual, incremental deterioration, we see the process accelerate uncontrollably before the Fed can fully react.

The other possible circuit breaker is slowing immigration. A few months ago I wrote about this possibility, which would entail a confusing mix of data (stabilizing/falling unemployment coupled with “weak” employment growth"). We haven’t seen any signs of this yet but it could yet materialize.

2. The Indicators

Three months ago I set a range of 4 primary indicators I’m using to track the ongoing cooling:

The unemployment rate

Nonfarm payroll employment

Hiring & layoffs from the JOLTS report

Prime-working age employment population ratio

On balance these data points have not looked good over the past few months. The unemployment rate has risen by 0.5-0.6 percentage points since early this year:

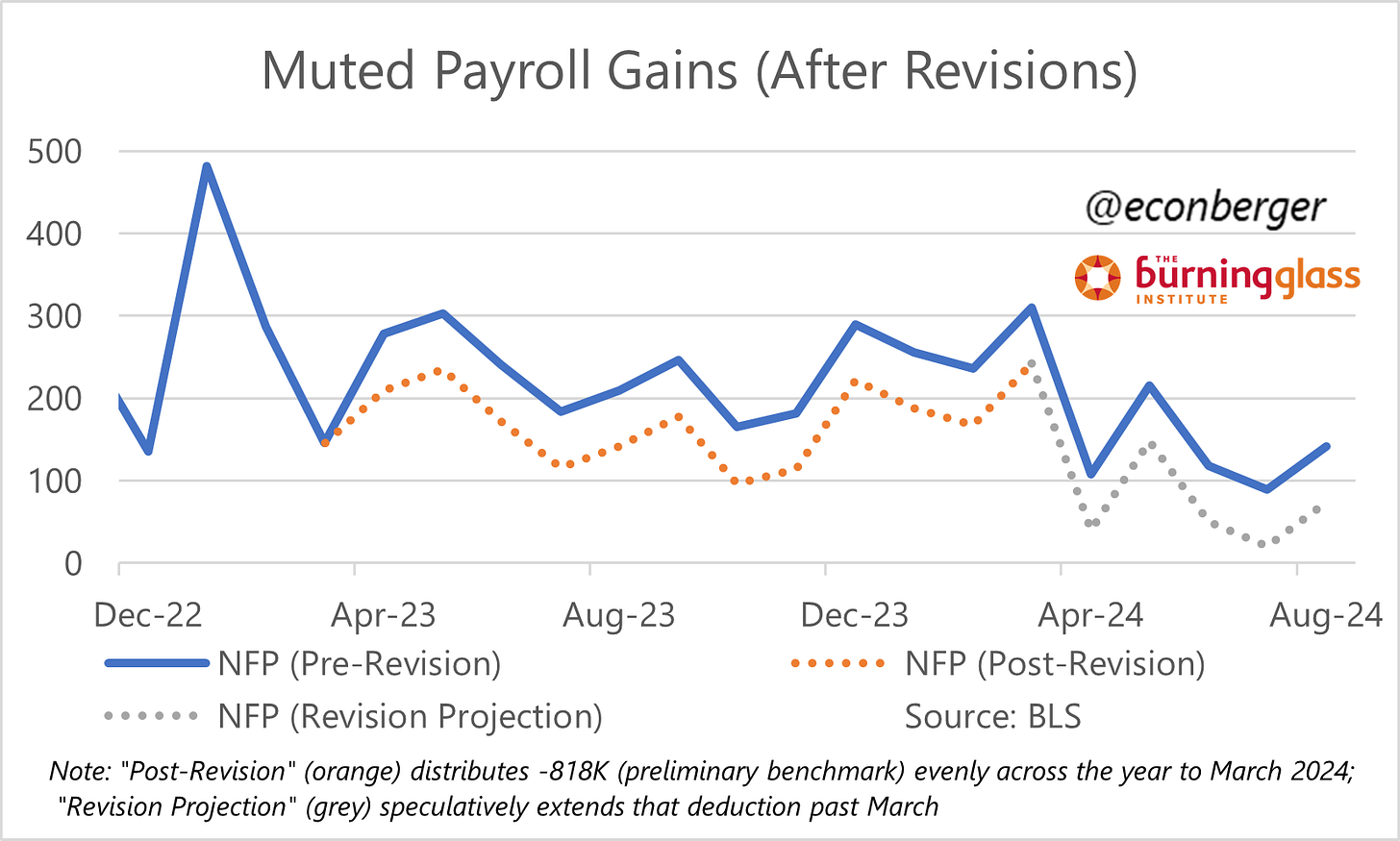

Nonfarm payroll gains have also moderated substantially. When considering the possibility of negative revisions to data post March 2024 (speculating here based on the preliminary benchmark estimate), forecasts of a September 2024 gain of 144K may actually mean a gain in the mid-to-high double digits.

Hiring and quits were soft in August. Hiring is now back to early 2010s levels, quits to mid-2010s levels. It’s very hard to find a job, and jobseekers know it.

Finally, the one bit of consistently good news (and general outlier) - the prime-working-age employment/population ratio is holding strong at 80.9%.

3. Some Things Are Different This Time

There are few features of current labor market cooling that look different than in past cycles.

The first is the ongoing “disagreement” between prime working age employment and unemployment. Typically these move in opposite directions. But in the current cycle, we’re seeing unemployment for this age group increase without an offsetting decrease in employment; on the chart below that shows up as a sideways movement rather than the more characteristic diagonal one.

The behavior of unemployment and employment for people in their early 20s is much more conventional - down and to the right. As far as these folks are concerned, we’re either in recession or getting close to one.

This odd split probably reflects what we see in the JOLTS data: a big decline in hiring coupled with very low layoffs, which protects people who already have jobs (including many prime-working-age people) but hammers people early in their careers. Prime working age employment metrics may have a blind spot.

The other interesting “different this time” is the composition of unemployment. Since the beginning of the year, the most recessionary component (“unemployed to permanent layoffs”) has not budged. Instead, we’re seeing an increase in unemployment primarily due to labor force entry - both due to new entrants and re-entrants.

I don’t think this development is entirely benign. If early-career folks can’t find jobs that’s bad; and generally re-entry in labor market downcycles is an echo of past job loss (it was the 2nd most important contributor to rising unemployment in the 2000-03 and 2007-09 labor market downturns). But it certainly is different!

> My baseline is that the unemployment rate will peak between 4.5%-5.0%

The “Sahm rule” or “Dudley rule” is the observation that since WW2, when unemployment rises by a small amount (say 0.5%), it then goes on to rise by a large amount (at least 2%).

Why would this time be different?