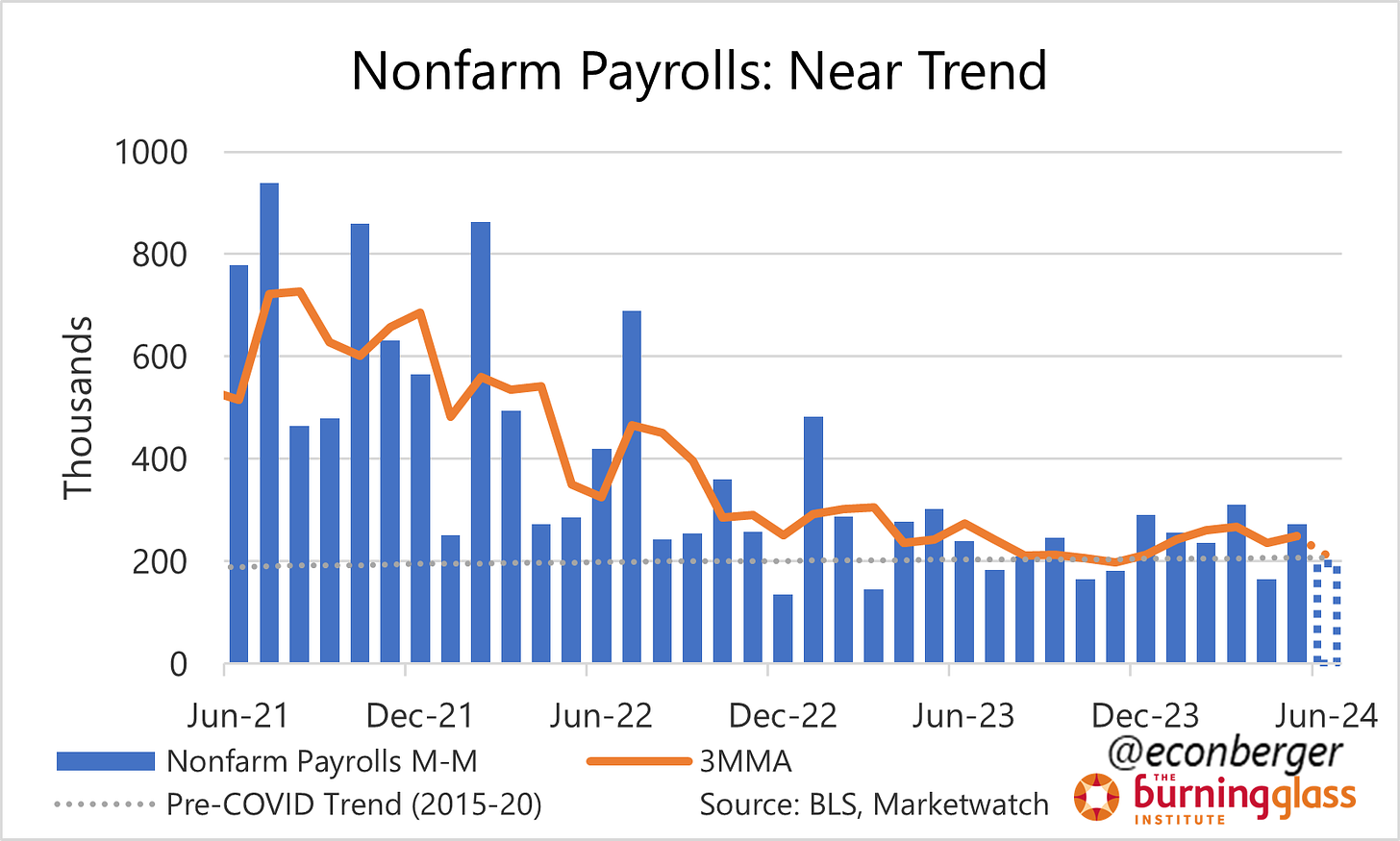

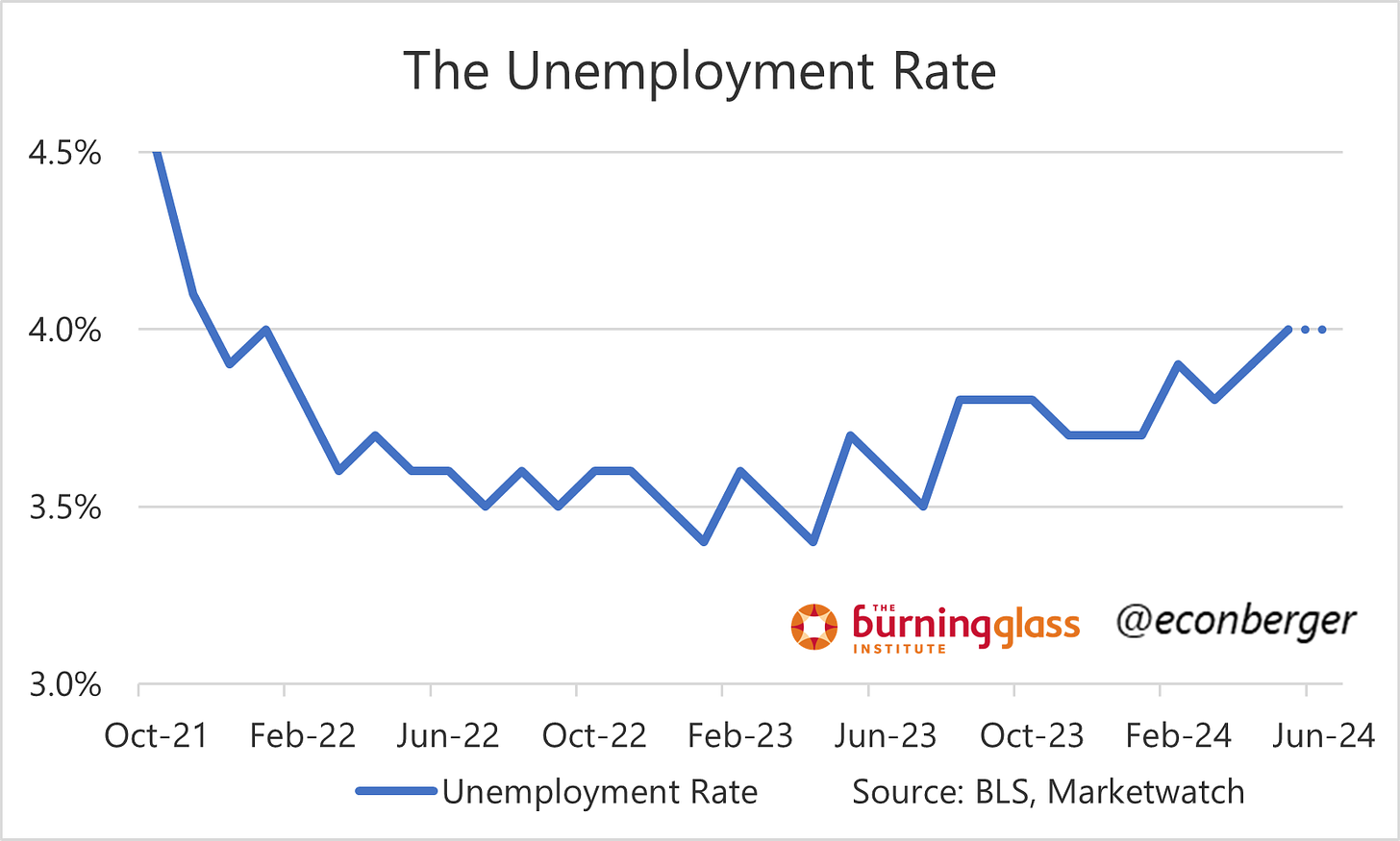

TL;DR: Forecasters expect another month of solid job gains in June, but without an improvement in unemployment.

In the rest of this preview, I cover:

The Big Picture

Labor Market Tipping Points

What Would Lead Me to Change My Mind

What If Immigration Slows

1. The Big Picture

We’re still looking at roughly the same constellation of data as we’ve seen over the past 6-12 months. The US labor market is:

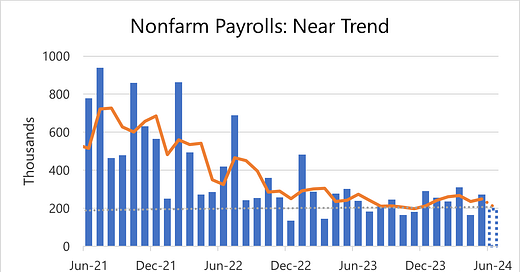

Not in recession, with solid (or better than solid) monthly job gains

Has cooled somewhat

Probably still is cooling

A. Labor Market Tipping Points

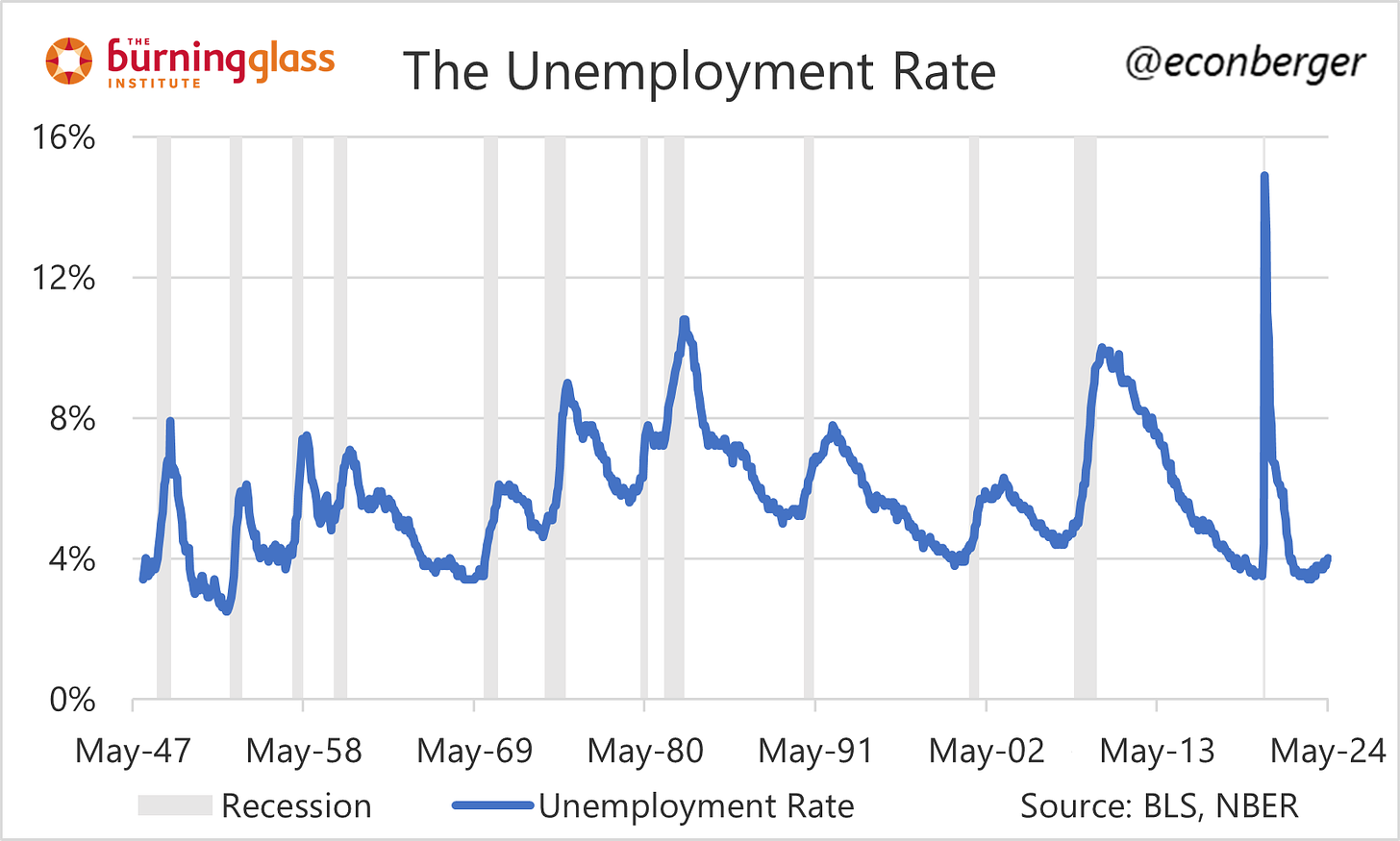

The biggest worry that’s nagging most practical macroeconomists: how do we know when a mild, non-recessionary cooling is at risk of tipping into a severe, recessionary one? The track record is not reassuring - most mild, non-recessionary coolings have turned out to be pre-recessionary coolings:

This is the logic that underpins the Sahm Rule. We don’t understand exactly what causes the switch to flip from “mild non-recessionary cooling” to “severe recessionary cooling” or how to predict it… it’s a sudden phase change, and one that policy hasn’t been historically capable of stopping right away, much less reversing. By the time you cross the tipping point, it’s too late.

If you’re hoping for ironclad reassurance that we’re not near a tipping point, you won’t find it here. But I think there’s some evidence against “we’re right on the edge”.

Let’s start with the risk of a switch from non-recessionary cooling to recessionary cooling. It’s a useful rule of thumb (not unlike the Yield Curve) based on a small n. But a hallmark of this cycle has been how different it has been - laying waste to all sorts of prior beliefs (like the Phillips Curve) about how the US (and global) macroeconomy works. I’ll talk about what makes this cycle different shortly, but for starters we should consider the possibility that this time is really different.

Now onto specifics: At least according to some significant metrics, the pace of labor market cooling actually slowed over the past year.

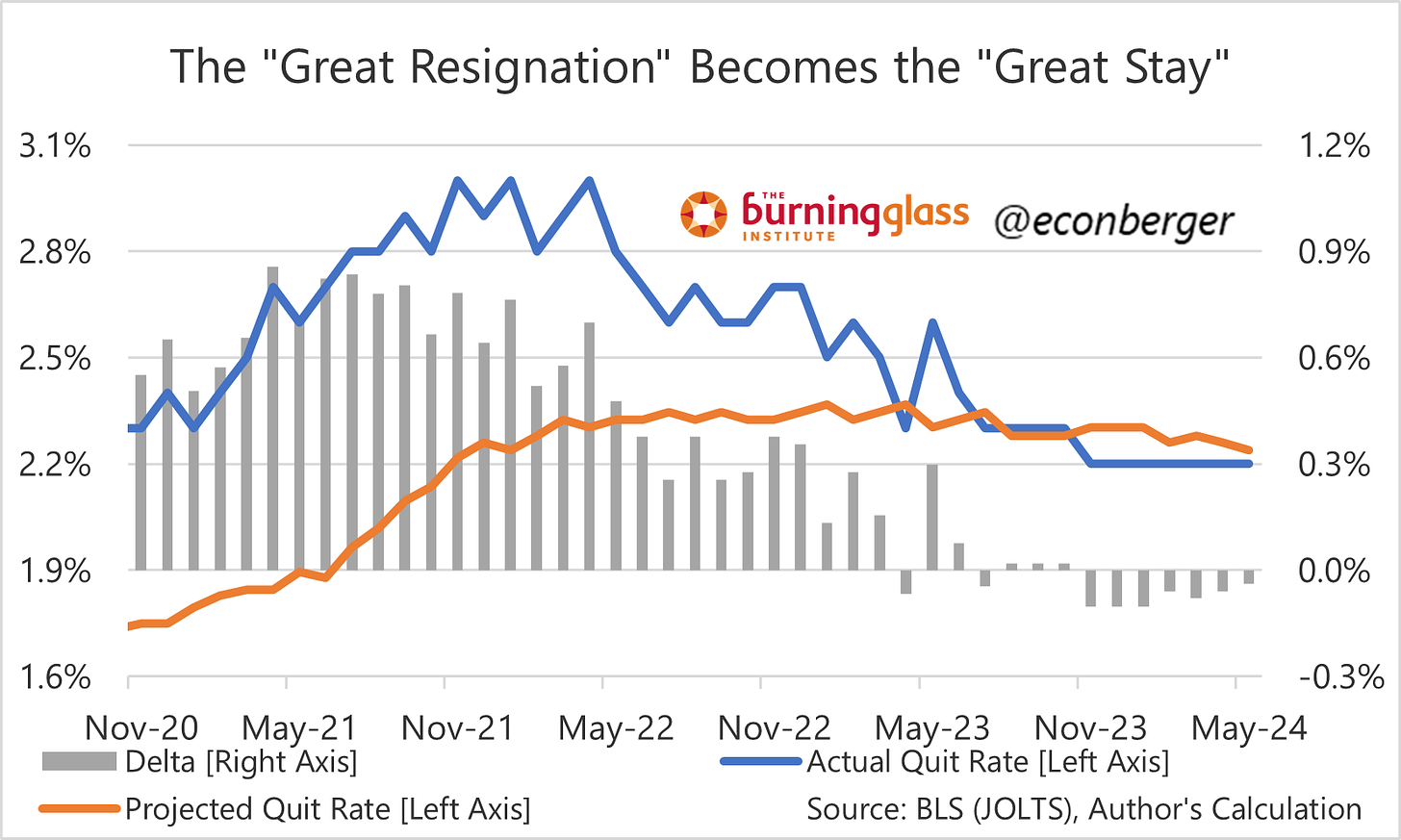

First, the JOLTS data we got this week confirmed that quits stopped falling earlier this year. (Recap here.)

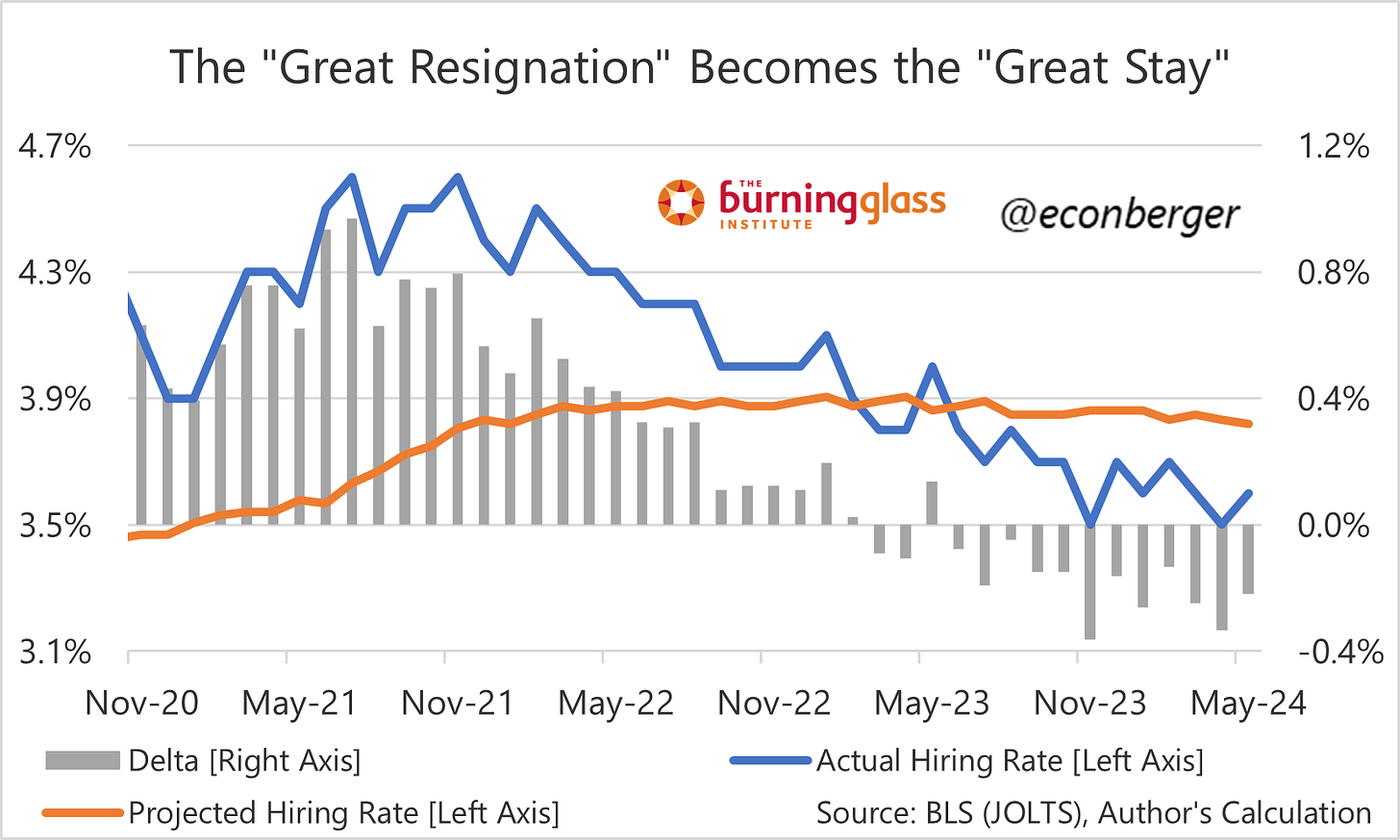

It also showed that the pace of hiring declines is moderating.

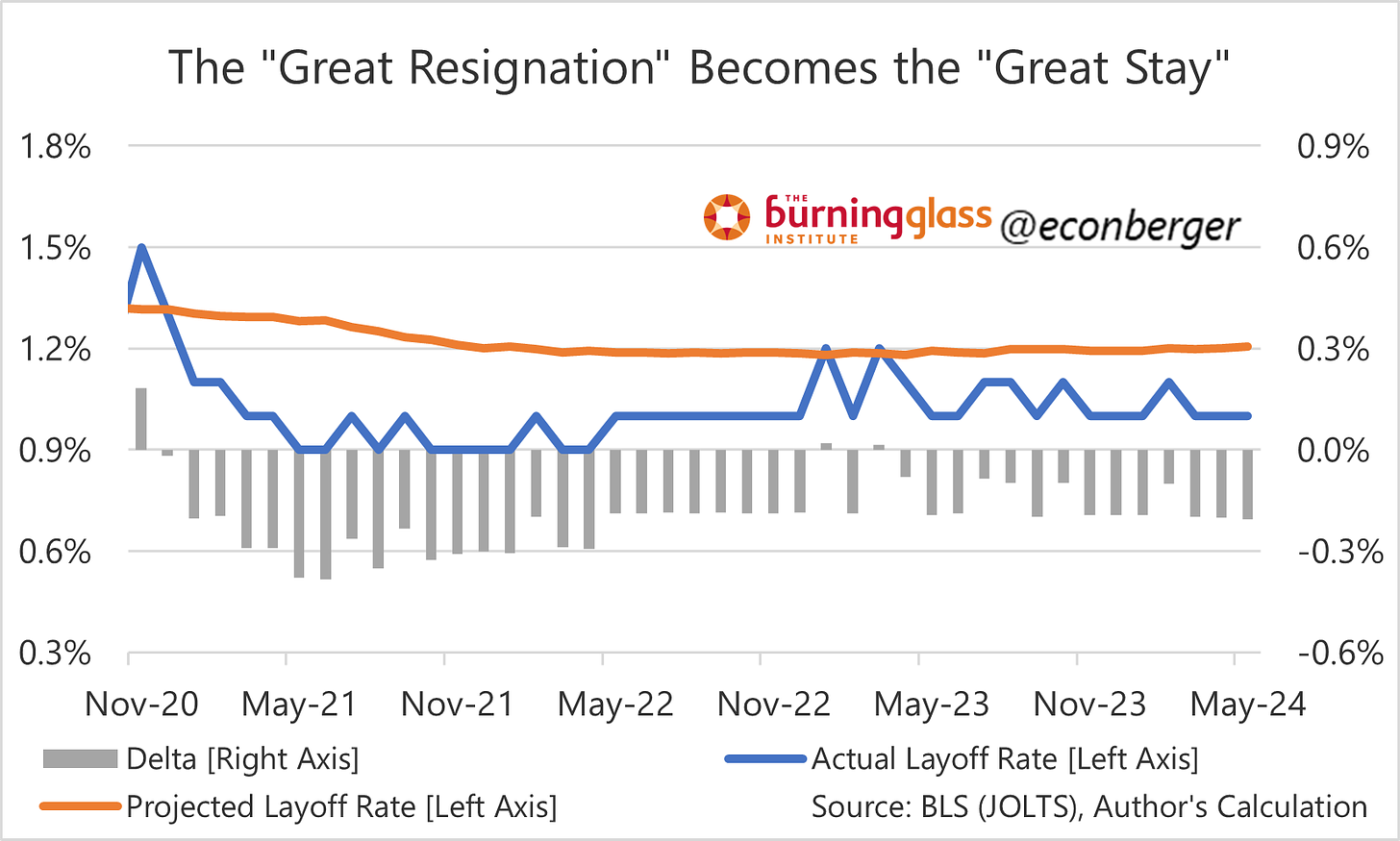

And of course layoffs are not increasing. This is in direct contrast to 12-18 months ago, when they did increase.

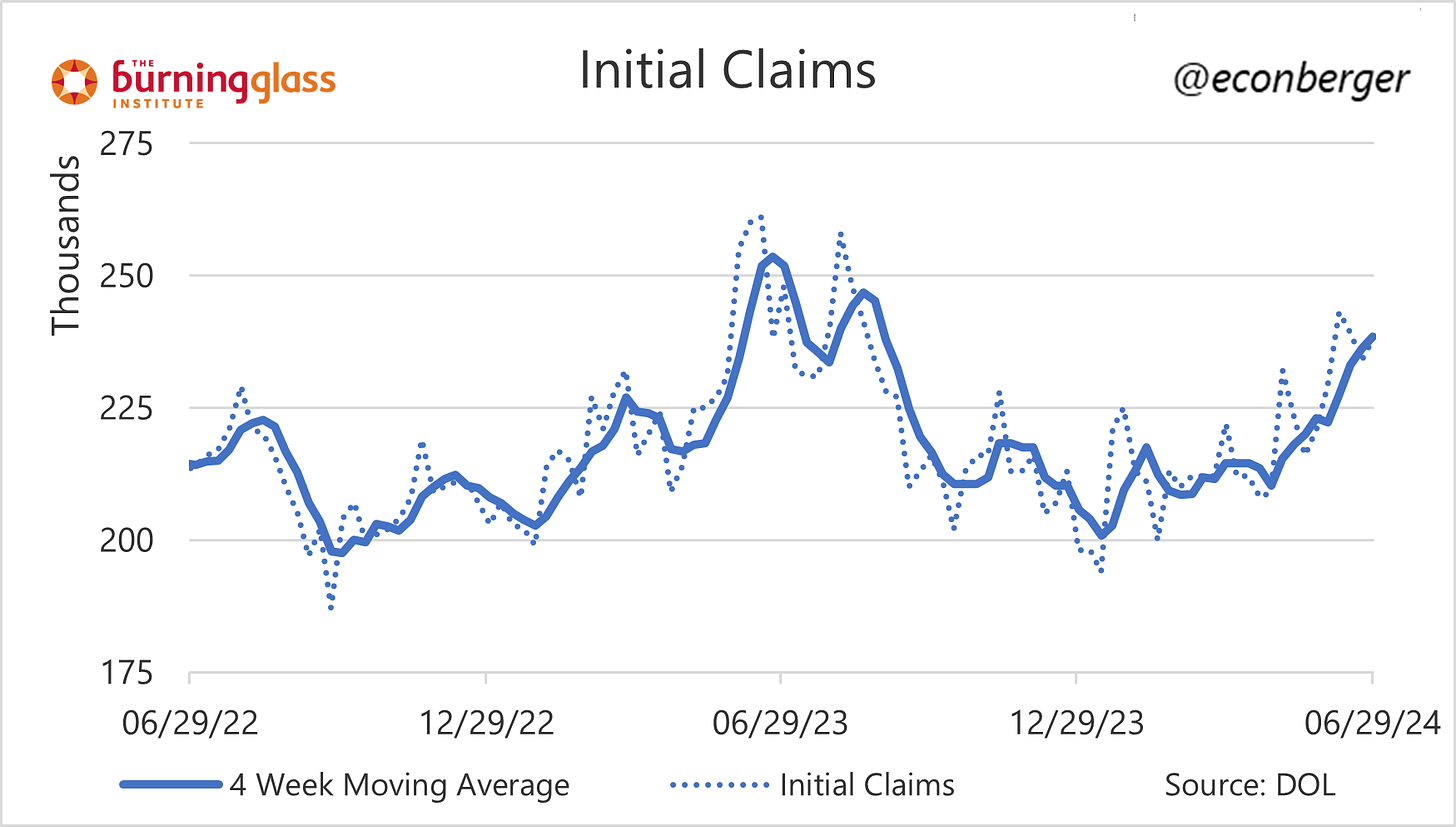

The unemployment insurance claims data has shown some short-term pickup recently, and is more timely than JOLTS. But even here, initial claims are lower than they were a year ago.

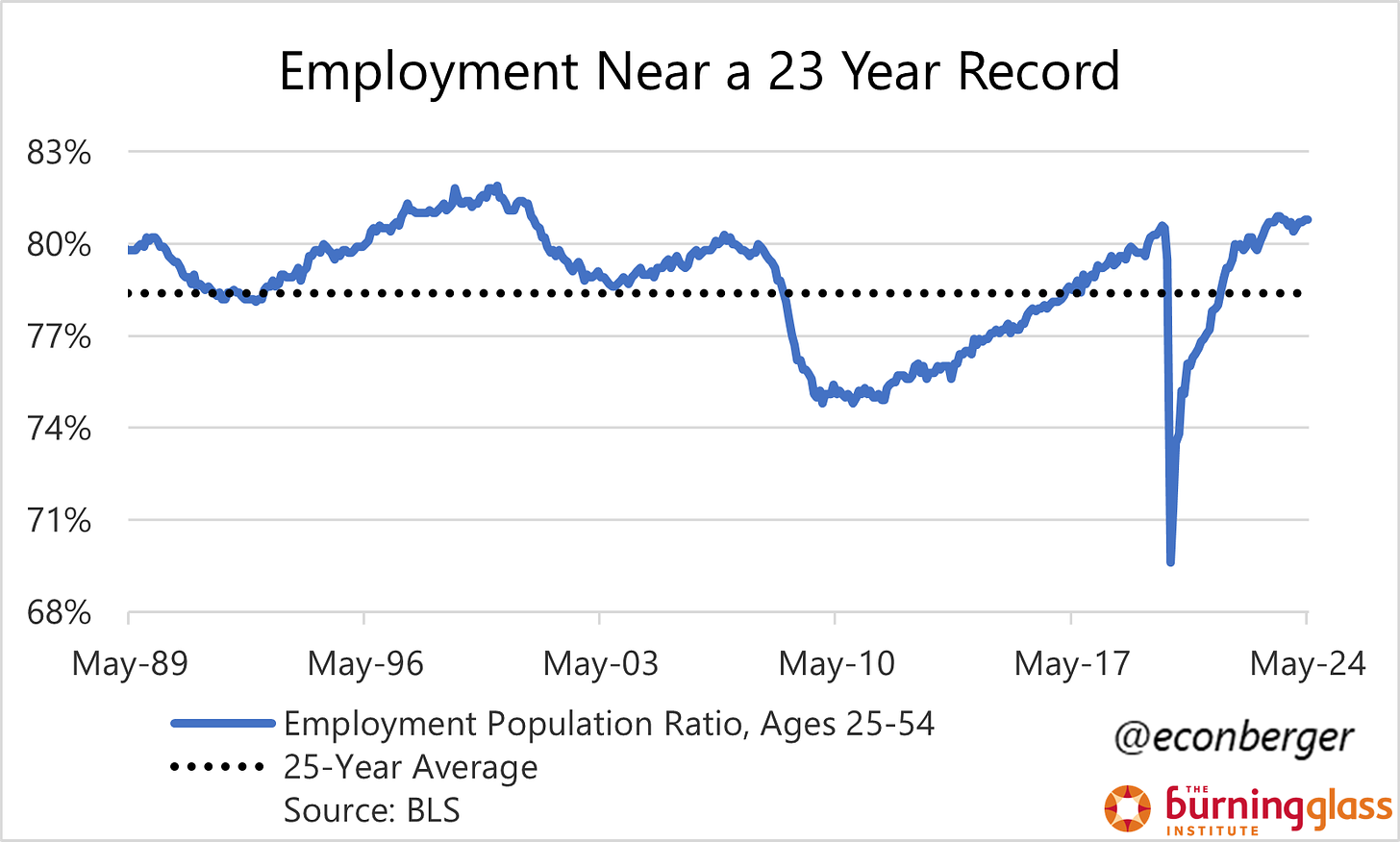

Prime-working age employment has not shown decline. It’s just flat, and a little higher than it was late last year. (On the disconnect between employment and unemployment: discussion here.)

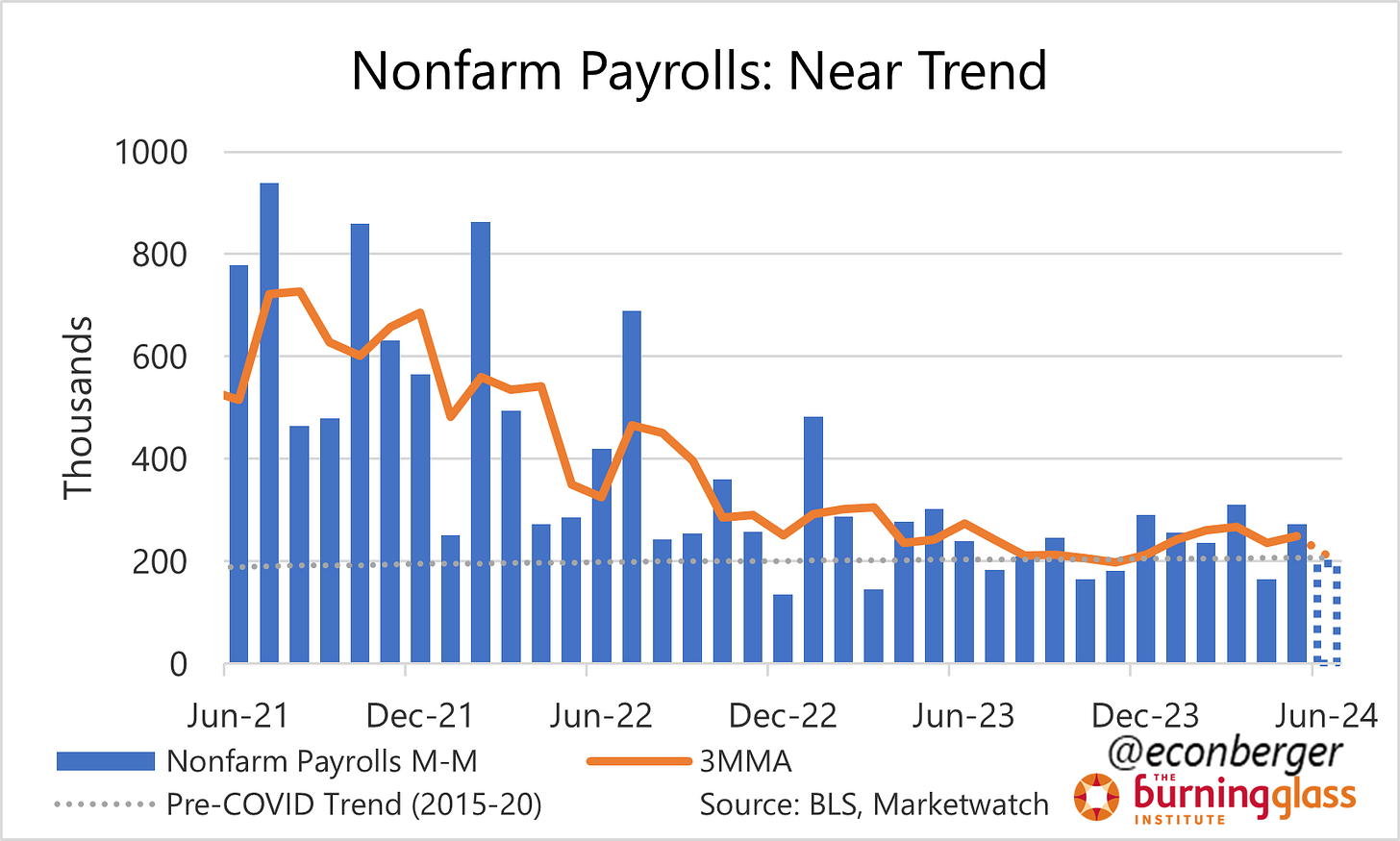

And it’s bizarre not to discuss nonfarm payrolls in this context. Negative revisions to this data are likely, but of a magnitude that will leave recent numbers as quite decent. Payroll employment declines are part and parcel of recessions (even pre-revisions). It’s not unprecedented to have a few positive monthly gains early in recessions, but not on a sustained basis.

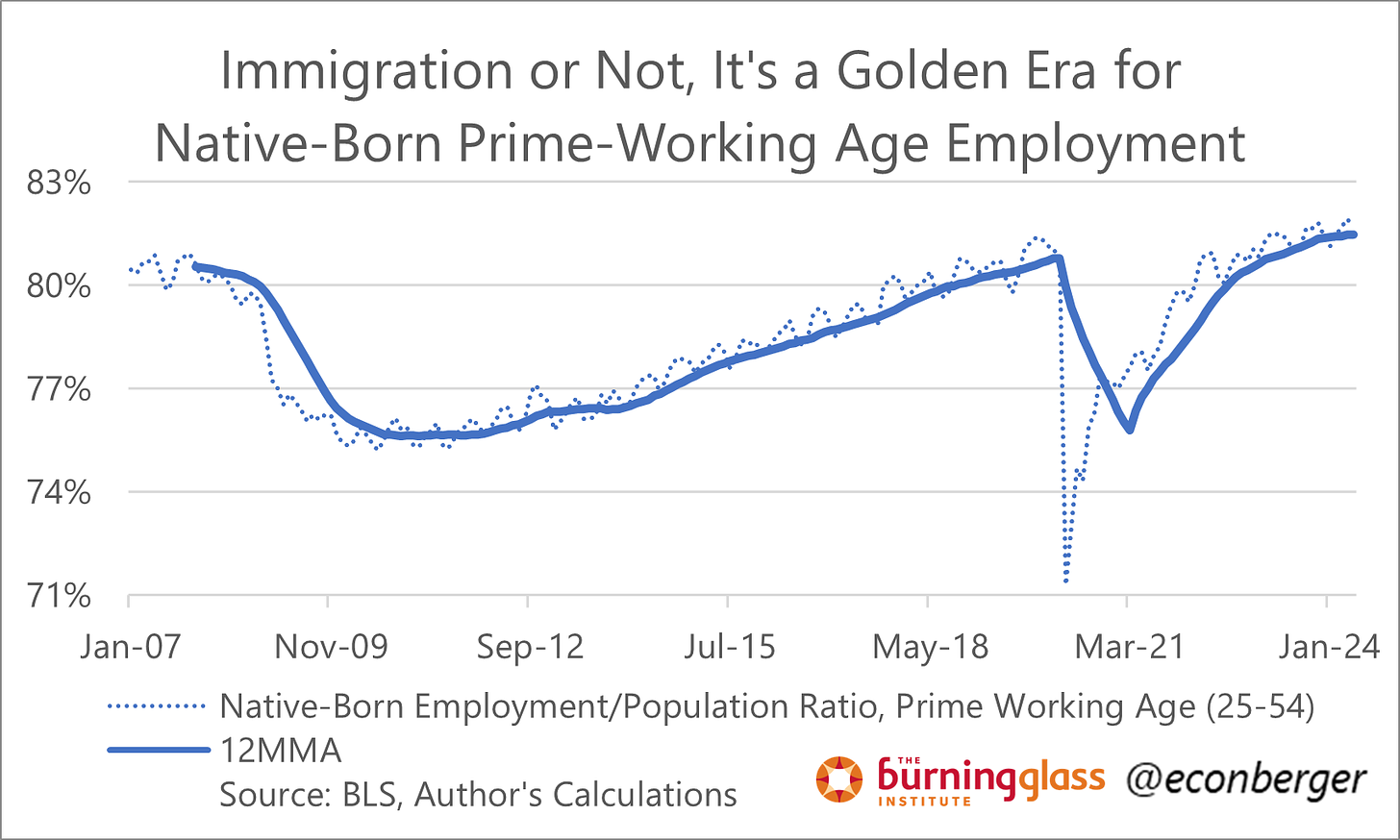

Zooming out, much of the cooling we have observed is driven by supply expansion - in particular, a surge in immigration. (I discussed this in detail on a prior substack.) A lot of the stories we tell about why non-recessionary labor market cooling turns into recessionary labor market cooling are demand-side stories, and it’s not clear those mechanisms apply at present.

B. What would lead me to change my mind?

So I don’t think we’re at the tipping point. But I’d caveat all my reassurances above with “at present” or “right now”. It doesn’t take a wild imagination to imagine small changes in the data over a few months that would make me more worried.

Top of the list would be consistent, ongoing increases in the unemployment rate each month. They don’t have to be individually large. For instance, if we’re at 4.3% by the September or October employment report, that would be fairly worrisome.

Another thing that would worry me: prime-working age employment, which has been more resilient than unemployment, showing signs of heading downward, in tandem with rising unemployment.

On the JOLTS data: if quits tilted downwards again, if hiring declines reaccelerated, or if layoffs picked up on a sustained basis into the fall (even by a little), that would be bad news.

And to wrap up, that solid nonfarm payrolls data (even with revisions): if it took a sudden lurch downward, particularly with ongoing gradual deterioration in the unemployment rate, would be a yellow/amber light.

Except for one possible twist…

2. What If Immigration Slows?

I’ve been fairly convinced for some time that immigration helps explain recently unusual behavior in the labor market data - in particular, strong employment gains coupled with a rising unemployment rate. Labor demand is expanding, but not enough to keep up with labor supply!

But of course the reverse is also possible. And it’s worth reflecting on what the data might look like if labor supply growth slows, but labor demand does not.

One possibility is that the cooling we’ve seen in data like unemployment and wage growth slows, or goes into reverse, even as nonfarm payroll employment also moderates. That data pattern would also be extremely confusing, much like the current one.

(I owe this provocative thesis to my boss, Gad Levanon, Chief Economist of the Burning Glass Institute.)

Great preview! Keep ‘em coming