TL;DR: My recent thoughts on 4 interesting labor market topics:

Immigration’s impact on the US labor market

Labor market outcomes for people in their early 20s

The recent divergence between employment and unemployment

The decline of corporate headquarters

I’d characterize my opinions on most of these topics as provisional or “in progress”. In some cases I have partially-baked theses; in other cases I have no hypothesis at all! But hopefully reading this provokes someone into providing the answers!

Topic 1: Immigration’s Impact on the US Labor Market

A particularly popular angle for labor market pessimists these days is focusing on the monthly changes in employment for native-born vs foreign-born residents of the US. For example, in May there were breathless headlines about the fact that native-born employment decreased by 663K whereas foreign-born employment increased by 414K. (Often, this leads people to draw the incorrect implication that “immigrants are taking native-born Americans’ jobs”.)

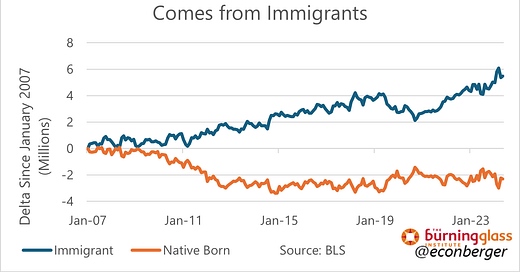

A useful bit of context, which I’ve previously discussed on this substack, is that the prime working age native-born population has not increased for at least 17 years, whereas the prime working age foreign-born population has grown by about 5-6 million over the same period (and by about 3-4 million since the pandemic).

In this context, it’s not surprising that you’d see employment of a demographic that’s expanding increase by more than employment of a demographic that’s staying at a fixed size.

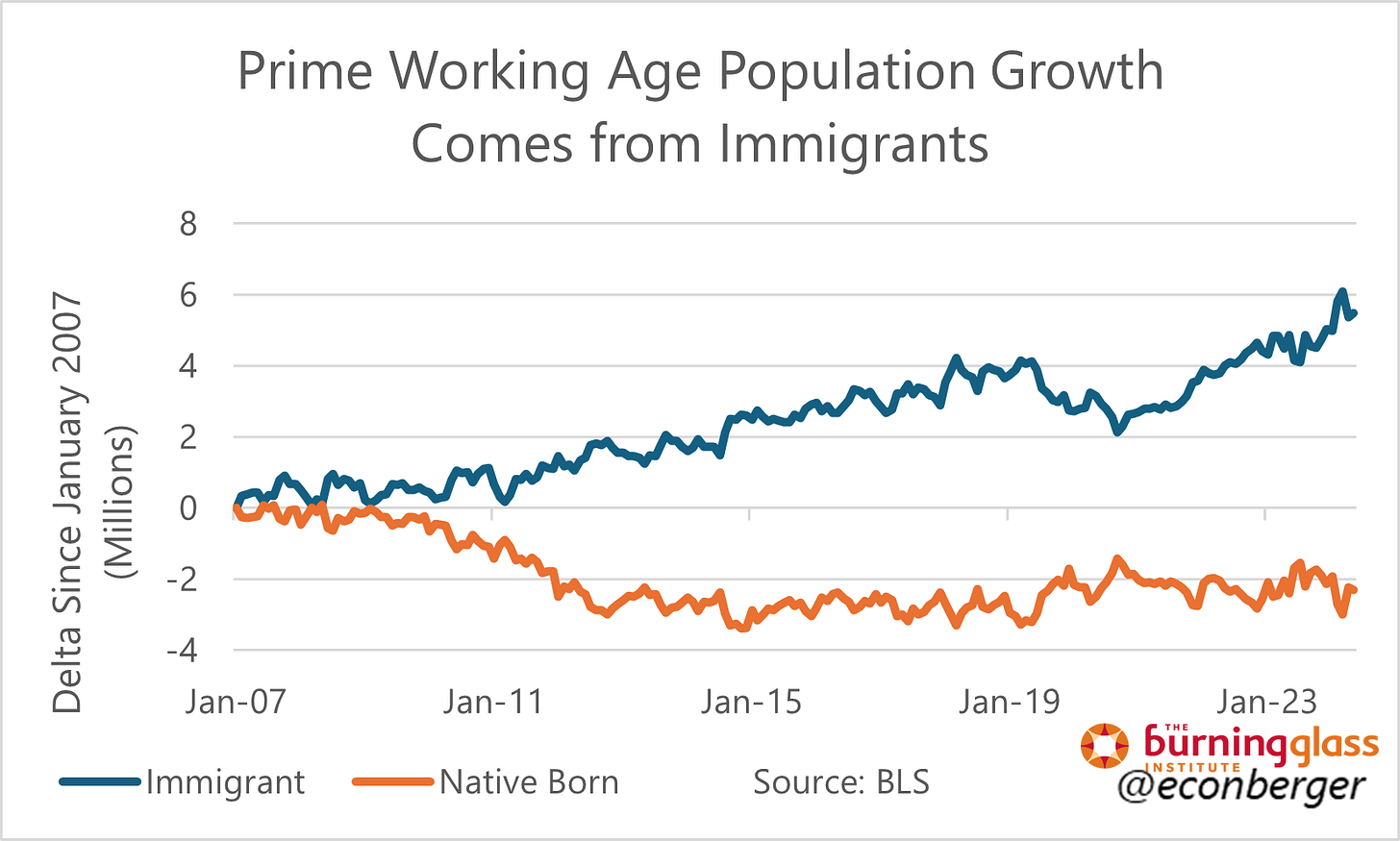

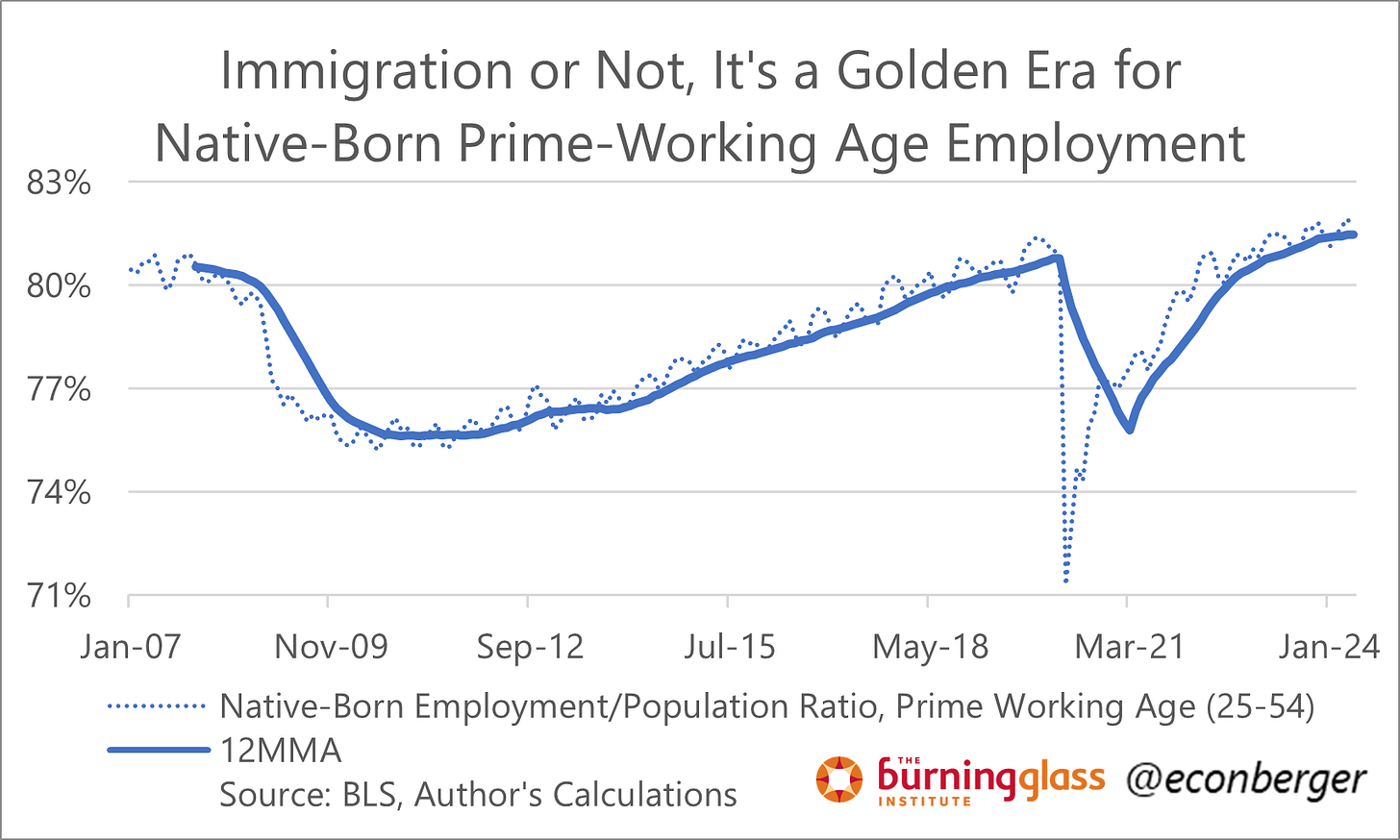

And in fact, what do you know? If you look at employment for native-born Americans of prime working age, the share of them who have jobs is now 81.5%, the highest since at least 2007. (Though the pace of increase has slowed.)

Where we do see a modest decline is in the share of foreign-born folks in the US who have jobs - a temporary result of a big wave of immigration which will gradually be absorbed into the workforce.

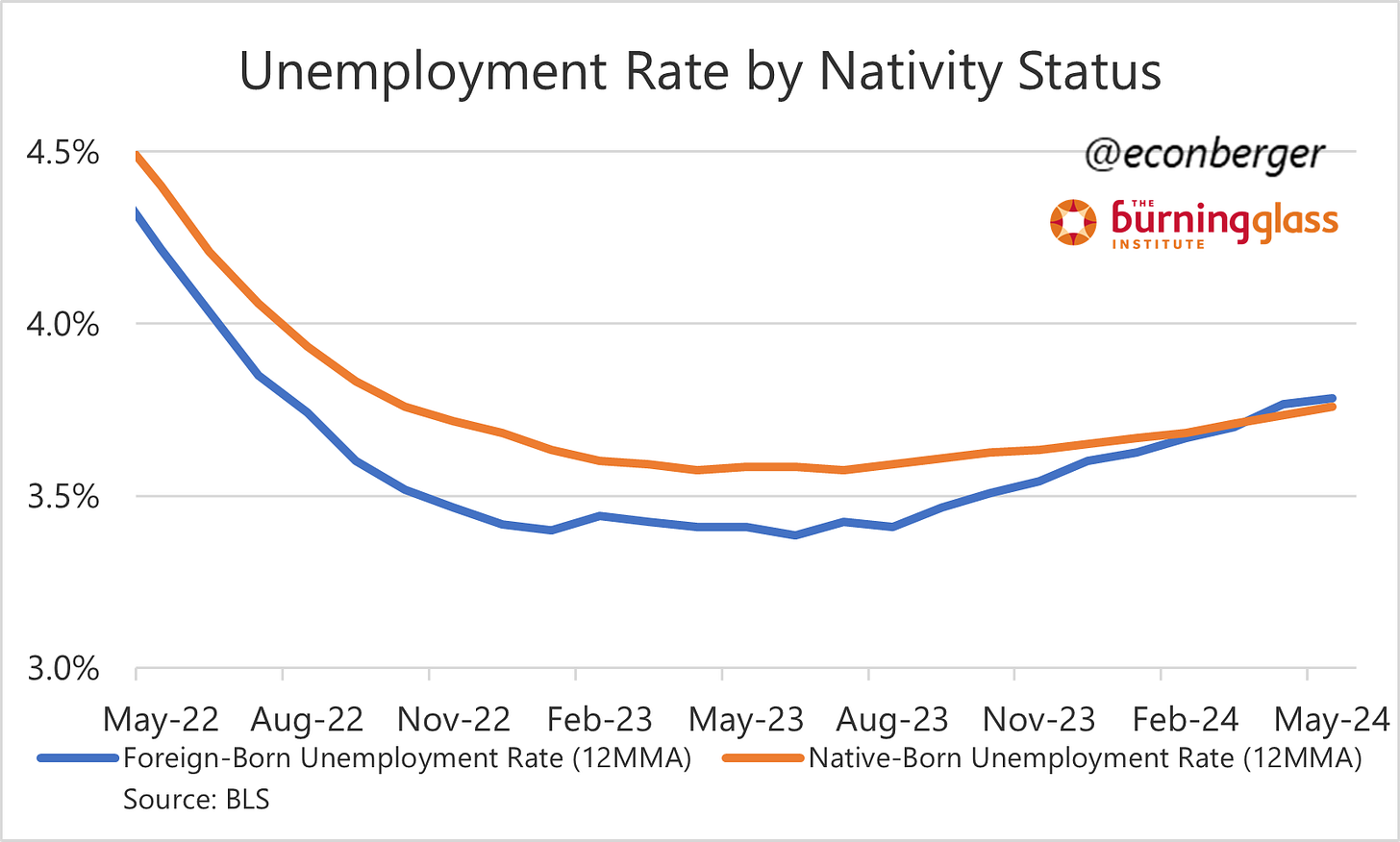

We also see this in the unemployment rates of the two groups - the cooling of the labor market (in terms of total unemployment rate increase) has been larger for immigrants than for native-born Americans:

There are more subtle/nuanced arguments this data doesn’t answer: would employment or wages for prime-working-age Americans have been higher in a counterfactual universe where immigration was lower? (Maybe we’ll find out soon, since American immigration policy is becoming more restrictive.) But at the very least, the claim that native-born Americans are “losing jobs to immigrants” in the commonly-understood sense is flat out false.

Final pedantic point: the native-born and foreign-born series by BLS are not seasonally adjusted, and show predictable seasonal patterns. So it’s a bad idea to calculate M-M changes for them. That warning goes beyond the general admonishment of “don’t put a lot of weight on M-M movements in household survey data”.

Topic 2: Labor Market Outcomes for People in Their Early 20s

May’s jobs report included a large increase in the unemployment rate for people under the age of 24. This led me to dig out a chart I’ve been using for several years, highlighting a pretty sharp split in labor market outcomes for younger workers. Post-pandemic, there has been a remarkable boom in employment for teenagers - the share of them with a job is the highest it’s been since the mid-2000s. But for early 20 somethings, even setting aside the May plunge (which may reflect seasonal adjustment quirks), the recovery has been lackluster and among the weakest of any age group.

When I first looked at the data, I assumed this was a story about rising post-secondary enrollment. But BLS data suggests the share of folks in this age group who are in school is actually falling. Early-20-somethings are working less, AND they’re studying less!

An interesting angle on this came from Joel Wertheimer, who pointed me to BLS data on unemployment rates for early-20-somethings by educational attainment. For those who have a diploma, an Associate degree, or “some college, no degree”, unemployment rates are generally lower than pre-pandemic. But for those who have a BA, the unemployment rate is actually a little higher than it was before COVID!

Someone asked me what’s causing this, and I’m not sure. Cohort effects caused by 2020 should be fading for this group. Weaker hiring in white collar sectors could be harming labor market entrants post-2022, though a lot of the relative softness for BAs predated the weak hiring phase.

Another theory is just that the economy is evolving in a way that has generated shortages for non-college-degree holders, but that either employers in these roles have been slow to look at BA holders or that BA holders are reluctant to consider these roles.

I’ll share more here as my thinking evolves.

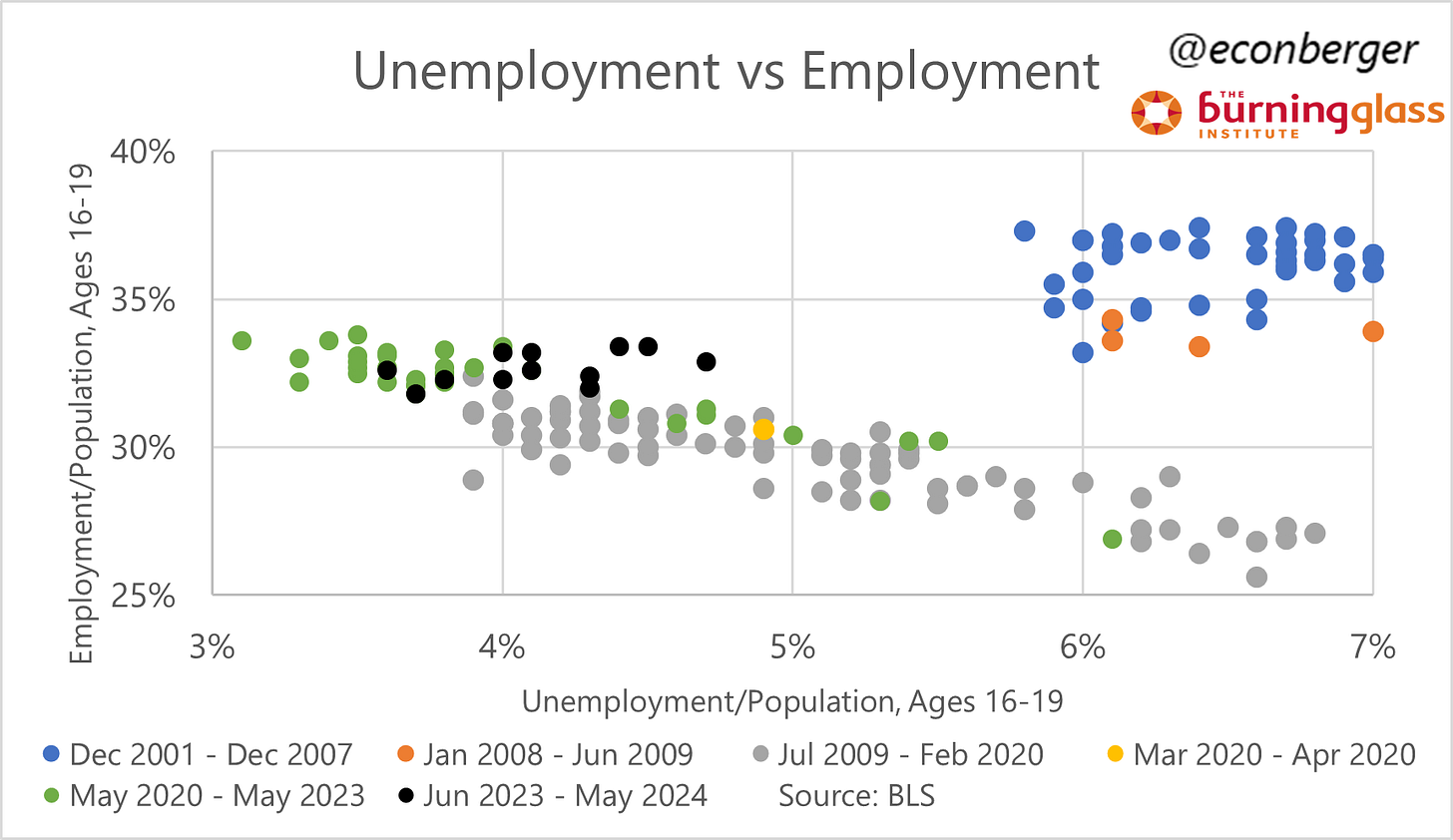

Topic 3: The Divergence Between Employment and Unemployment

We’re used to thinking about employment and unemployment as being inversely correlated in the business cycle. When times are good, employment (unemployment) goes up (down); when times are bad, employment (unemployment) goes down (up).

But over the past year, that’s not what’s happened. Prime-working age employment AND unemployment both went up a small amount. What’s going on?

I took a look at the historical relationship, and it’s not always stable. In the 2001-09 period (blue and orange dots), there was a higher steady state level of unemployment for any given level of employment (and vice versa). In the 2010s and very early 2020s (grey, yellow, green), there was a lower steady state level of unemployment for any given level of employment.

This means the increase in unemployment is a little more ambiguous than usual. Maybe it’s going back because a surge of recent immigrants are actively looking for work. Maybe the strong labor markets of the late 2010s and early 2020s means folks without a job have more confidence about finding a new one than their peers 5-10 years earlier. Or maybe the cost of actively searching for a job has fallen with the increase of easy-apply-online options.

For what it’s worth, and tying back to the second section of this email, we don’t see the same pattern for people in their early 20s. Their employment/unemployment relationship has remained unchanged. (Which I think adds some probability weight to the “strong labor market increases the perceived value of job search”.)

BUT… we do see a similar pattern for teenagers as for prime-working-age adults; and teenagers have arguably experienced the strongest post-pandemic labor market of all!

Topic 4: The Decline of Corporate Headquarters

Of all the topics in this summer special edition, this is the least evolved. Would love some ideas!

It’s usually ignored within the BLS jobs report, but there’s an industry within “professional and business services” that’s called “management of enterprises and companies”.

This highlights an underappreciated feature of the establishment survey: it classifies employer industry by establishment, not by company. So a given company can straddle several establishment, and a company with “non-production” headquarters can include at least one establishment that’s in this “management industry”.

This industry’s employment as a share of nonfarm employment has fallen pretty sharply over the past year or so!

I’m not sure what’s happening here. The last time we saw a sustained decline (aside from the COVID period, and a flat period in the mid-2010s) was the 1990s. A few hypotheses that may or may not be supported by a further deep dive into the data:

A surge of small business formation is driving a decrease in the share of corporate headquarters employment (since most of these small businesses don’t have a separate headquarters establishment)

Businesses are becoming more decentralized by opening more regional offices, branches and franchises.

Businesses are intentionally shrinking headquarters.

Any other ideas?

headquarters are overhead, and ripe for the kinds of jobs that can be automated. Perhaps some of the recent productivity surge is at the expense of highly paid administrative workers at HQ.