I’ll publish 3 pieces this week: a JOLTS recap (this one), a BLS jobs report preview (later today) and a BLS jobs report recap (Friday).

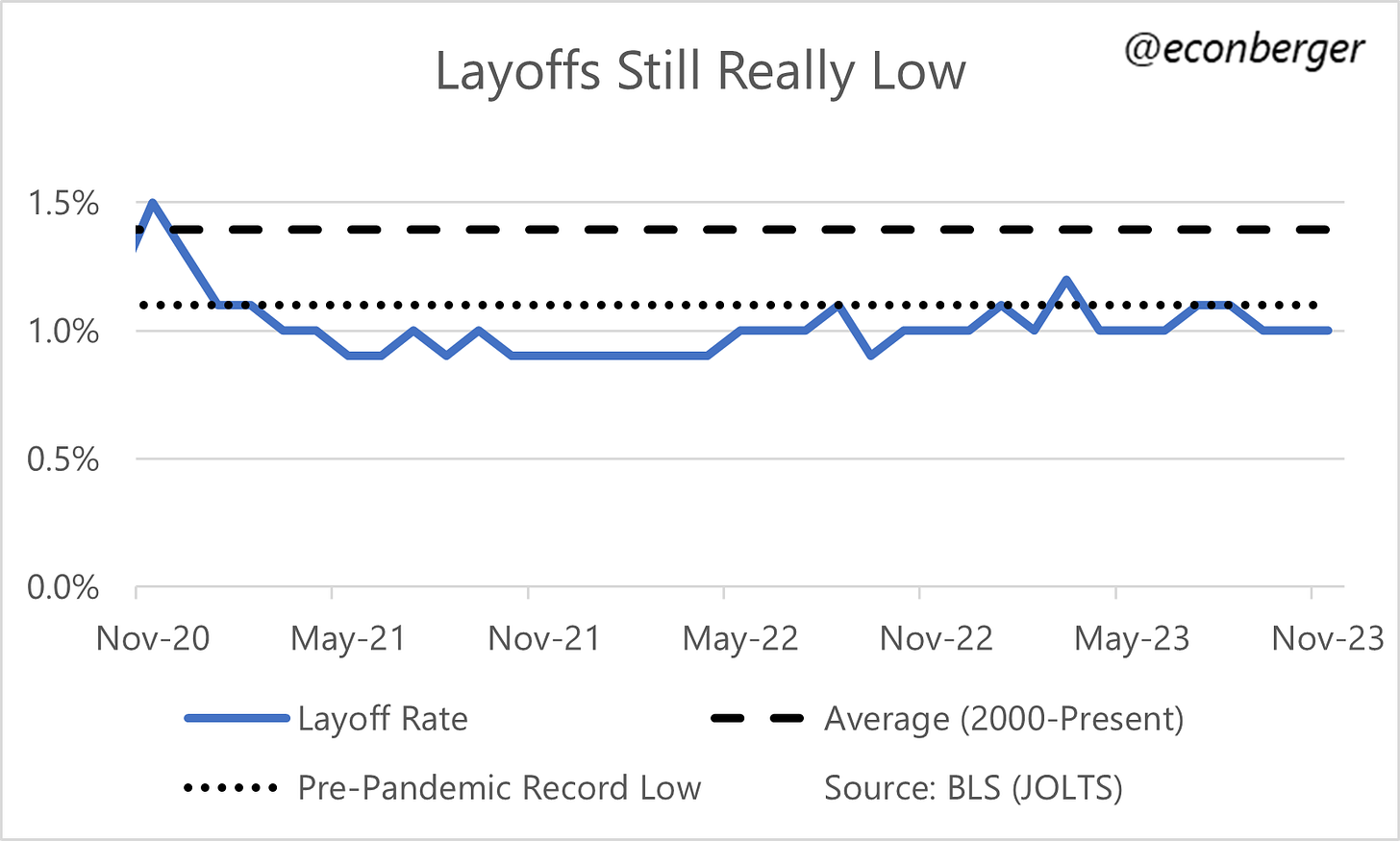

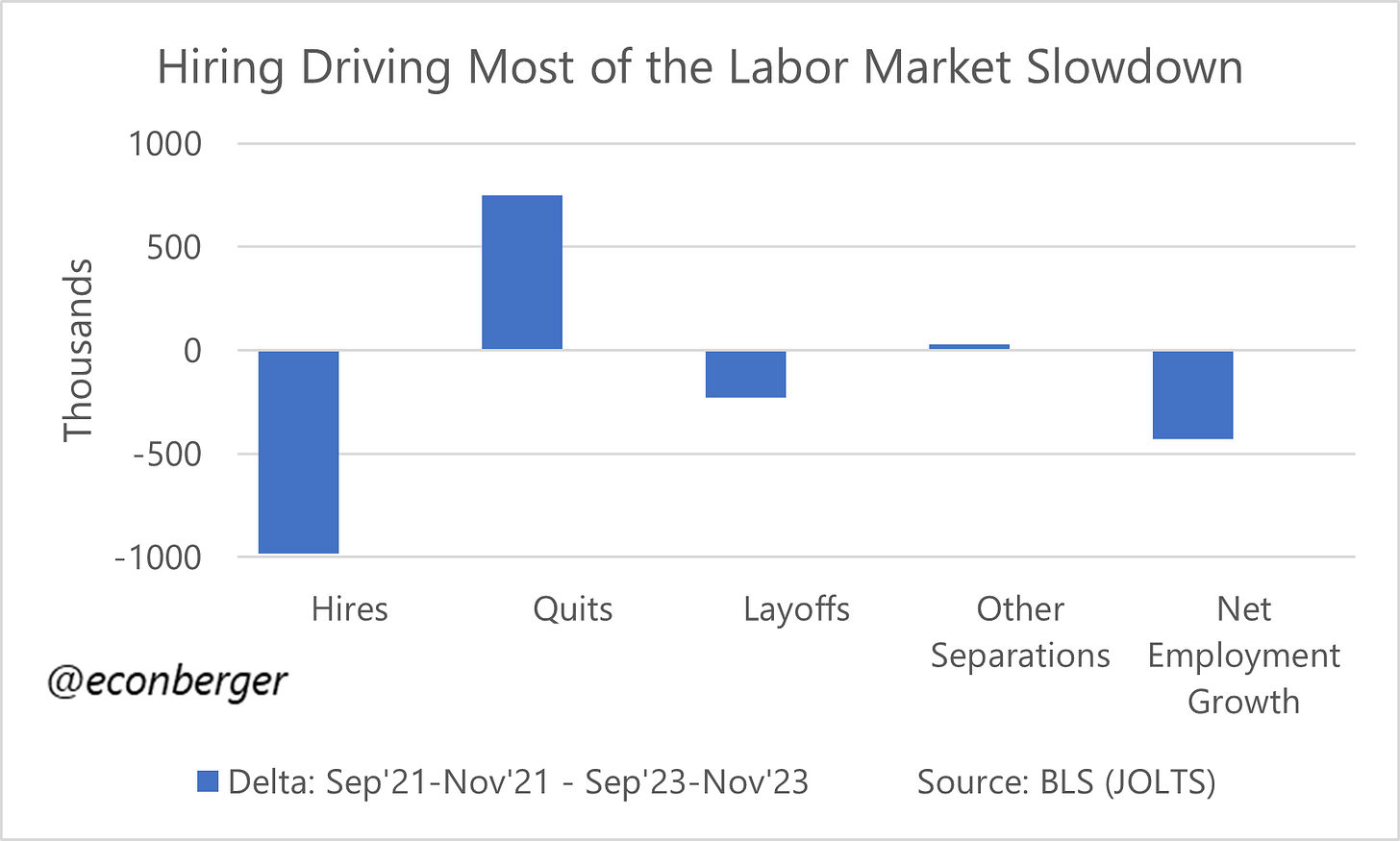

TL;DR: Hiring and quits both declined to their lowest levels since 2020, and are now at levels consistent with an unemployment rate higher than 4%. Layoffs remain very low by historical standards.

In the rest of this piece, I’ll discuss: (1) Hires and Quits, (2) Layoffs and (3, reluctantly) Openings.

More below chart.

1. Hires and Quits

Yesterday, with characteristic foolishness, I tweeted about how key metrics in the monthly JOLTS report had stabilized since the summer and that I anticipated that would probably continue:

JINX! The vengeful macro gods traveled back in time and slipped some humbling data points into today’s report.

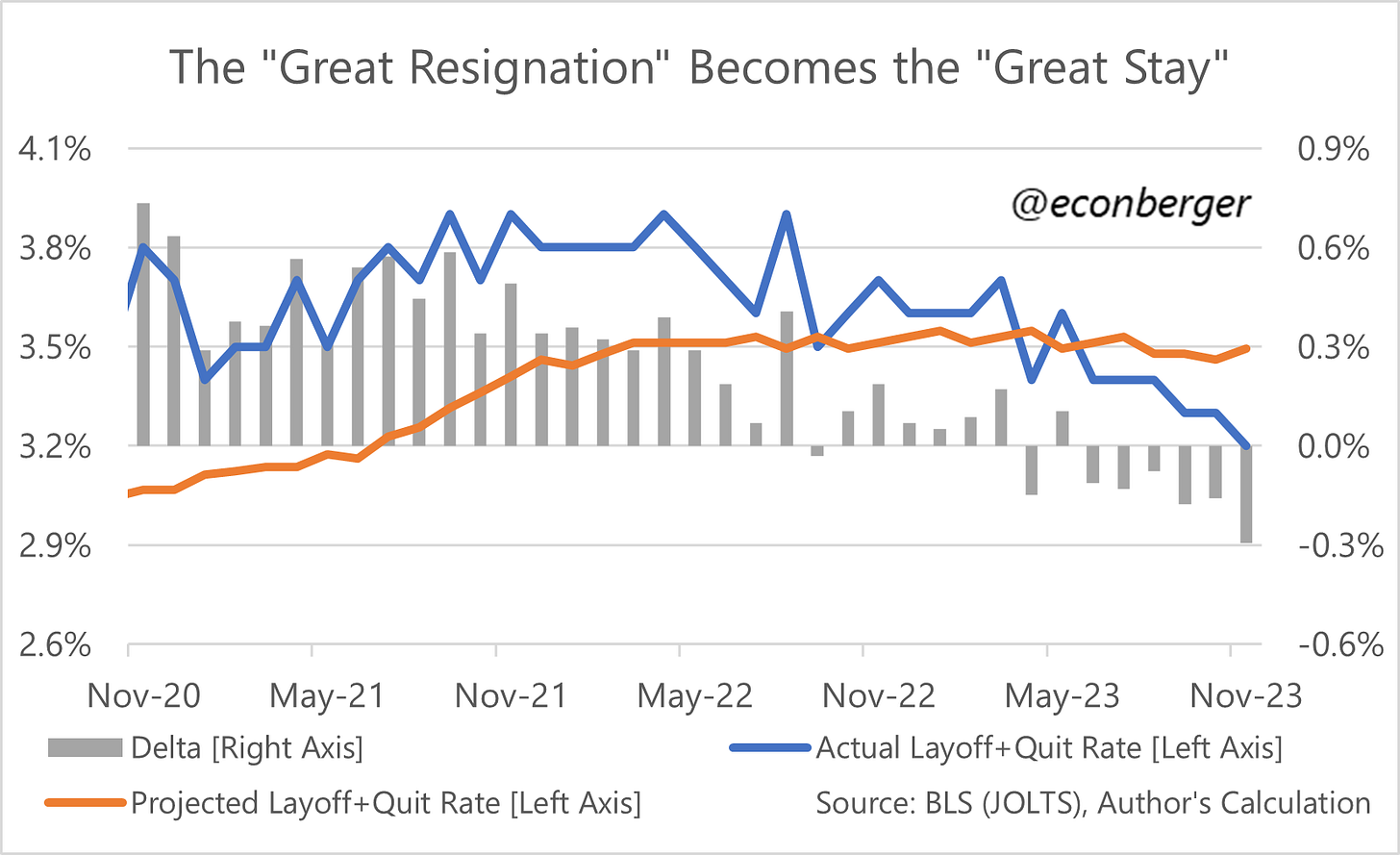

The hiring rate fell to 3.5%, the lowest since March 2020 (and, excluding the pandemic, the lowest since 2014). It’s now far below what we’d expect with an unemployment rate of 3.7% - more like what we’d expect with an unemployment rate of 6.5%!

The quit rate fell to 2.2%, the lowest since September 2020 (and, excluding the pandemic period, the lowest since 2018). It’s now a little below what we’d expect with an unemployment rate of 3.7% - more like what we’d expect with an unemployment rate of 4.2%.

Other smart commentators have expressed concern about what these declines mean for recession risk. I’m not super-worried along this front, for three reasons:

It could be noise.

We already have other data that doesn’t demonstrate the same pessimism (the November jobs report, claims).

Unemployment has been disconnected from these metrics for more than 3 years.

So I recommend against a strongly-held belief “since hiring and quits are unusually low relative to unemployment, unemployment is going to increase”. In the current environment there’s an extraordinarily wide range of turnover behavior consistent with sub-4% unemployment.

But that doesn’t mean these developments are benign from a worker’s perspective. For instance, as Arin Dube points out, to the degree that turnover is a key element of wage growth, it may mean that pay increases are headed down further. (The Fed might not find it as objectionable as workers do!)

One final, funny note on quits. In early November, Chip Cutter of the Wall Street Journal published an article titled “The New Headache for Bosses: Employees Aren’t Quitting.” At the time, the most recent data we had in hand was September’s and I observed that quits were right in line with what you’d expect from the unemployment rate. But in November’s data, that was no longer true: quits were too low. Chip’s article was a nowcast for the November JOLTS data!

2. Layoffs

So hiring and quits were disappointing, but layoffs held steady at 1.0% - very low by historical standards, and lower than at any point in the pre-pandemic period. At the current unemployment rate, given behavior last cycle, you would expect a layoff rate of 1.2%.

We’re experiencing an unusually benign mix of separations right now. They’re the lowest they’ve been since 2016, and consistent with an unemployment rate around 5.5%. But in 2016 the layoff rate was lower, and the quit rate was higher. In a prior essay I discussed possible explanations - labor hoarding is one, misclassification is another.

Because layoffs have been so muted, the main dynamic in labor market cooling over the past 2 years has been the decline in hiring.

3. Job Openings

If you read my work you know I’m not a big fan of this indicator. The best thing that can be said about it: if you correct for a bunch of problems with it (most significantly, an upward trend that doesn’t reflect macro conditions), it probably tells you what you already know from quits and hires.

But in case you’re curious: it was stable in November. Taken too literally, it (probably erroneously) suggests the job market is much hotter than it was before the pandemic.

Great summary, thanks Guy!

Low Wage Workforce Tracker

Shining a light on the U.S. workers paid the least

https://www.epi.org/low-wage-workforce/