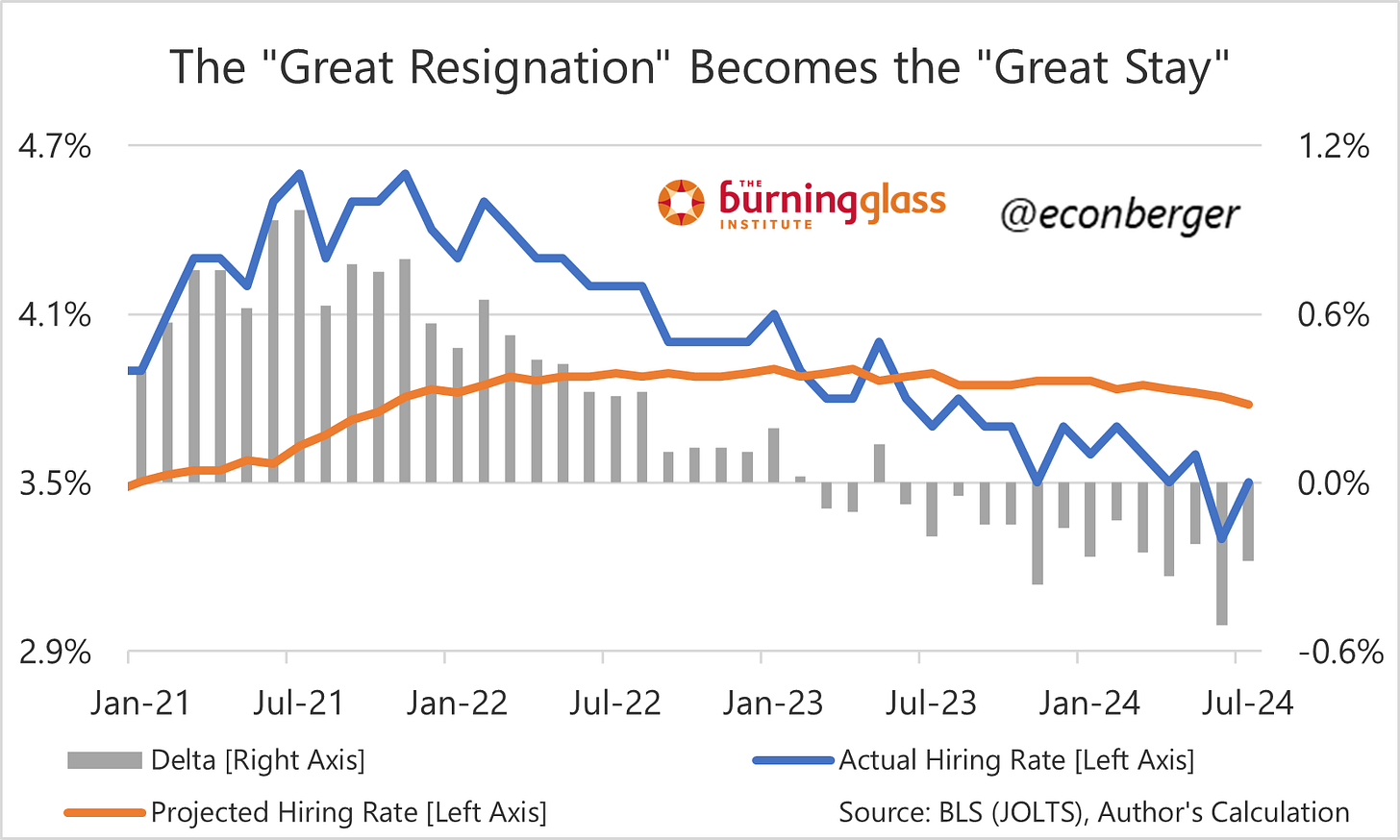

TL;DR: Though the July JOLTS data incrementally improved relative to its June predecessor, the underlying trend continues to show cooling: lower hiring and quits.

In this recap I talk about:

The Big Picture

The Beveridge Curve

1. The Big Picture

The unemployment rate is at 4.3% - quite a bit higher than a year ago, but still relatively good by historical standards. Unfortunately, from a job seeker’s perspective, that paints an overly rosy picture. It’s a hard time to find a job, and gradually getting harder.

The hiring rate clocked in at 3.5% in July. This was an improvement from June’s 3.3%, but is still fairly soft - in the past cycle, it would have been consistent with an unemployment rate around 6.5%. Or alternatively, hiring is now at early 2014 levels. That wasn’t a terrible job market, but it wasn’t a great one either.

The picture portrayed by quits isn’t so downbeat. The quit rate was 2.1% in July, consistent with an unemployment rate at 4.7% - around where the labor market was in late 2016 or early 2017. But that was a period of gradual improvement in the labor market, and unfortunately we’re currently headed in the opposite direction.

Finally, the one ongoing bit of good news from this report is layoffs. They remain very low by historical standards and show no signs of increasing.

Unfortunately, while it’s nice to have ongoing good news from the layoff front, it doesn’t change the overall message of the JOLTS report - which is the labor market is moving in the wrong direction. It does not take an increase in layoffs for unemployment to rise - even a small ongoing flow of job loss can turn into a bigger problem if these unfortunate folks have hard time finding new opportunities.

2. Beveridge Curve

The Beveridge Curve is the relationship between job openings and unemployment. The Curve isn’t particularly stable over time - it’s shifted from cycle to cycle - and during the Great Resignation of 2021-22, we were far far above the 2010s Curve.

For the first year of labor market cooling, from the spring of 2022 through the spring of 2023, we experienced an “immaculate cooling” of the labor market - job openings (related metrics, like hiring, quits and wage growth) cooled significantly with no adverse effect on unemployment.

Over the past year, the cooling has become a little more “maculate” - the unemployment rate has crept up (light blue dots) and in general we’re seeing more of that traditional Beveridge Curve downward slope. Cooling the labor market has become more costly.

The good news is that the Fed doesn’t want to see any more labor market cooling, and will recalibrate policy accordingly; the less-good news is that, even if they act now, there might be at least a little more cooling baked in during the remainder of the year.