Internal Mobility: The Hope That Never Materialized

It's Fallen, Just Like Regular Turnover

I’ve been serving as the Workforce Economist in Residence at Guild since the summer, and this is my deep dive on data from Guild and Lightcast’s recent Talent Resilience Index (TRI) report. I appreciate them sharing this data with me!

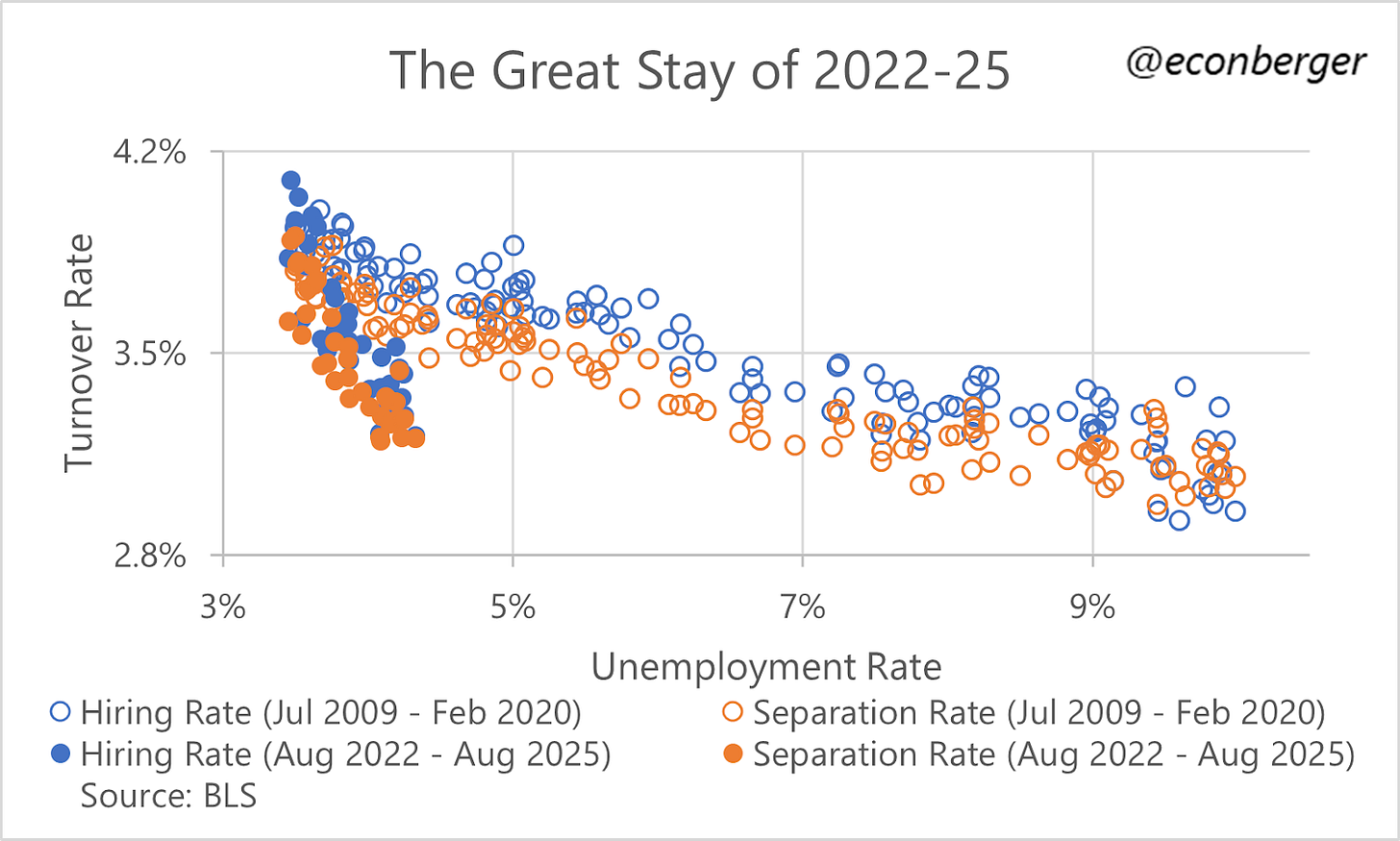

For as long as I’ve been writing this substack, I’ve been writing about “The Great Stay”: hiring and separations are unusually low by historical standards (first time; most recent). Typically, turnover has an inverse relationship with unemployment - when the labor market is hot, people tend to job hop more and employers have to hire at a faster clip; when the labor market is cold, workers “hug their jobs”, reducing employers’ need to hire. But that relationship has shifted relative to historical patterns. In October 2025, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the hiring and separation rates (job starts and endings as a share of employment) were at 3.2%, comparable to where they were in the early 2010s. The twist: in the early 2010s, the unemployment rate was north of 8%; today, it’s around 4.5%.

Lower turnover is beneficial in some ways, but also creates problems. Turnover is one route through which firms traditionally reprioritize in response to market shifts is by hiring people with skill sets that are internally lacking; and to a lesser degree, letting people go (via attrition or, more rarely, layoffs) when their skill sets are in internal surplus.

Of course, that’s not the only way for firms to reorient their composite skill set. They can also transform their existing workforce via reskilling and retraining. Let’s say you’re a car dealership with two types of workers, salespeople and mechanics. If you have too many salespeople and not enough mechanics, you can hire more mechanics and gradually shrink your sales force; or you can retrain salespeople with mechanical skills. In principle, turnover and internal reallocation are substitutes.

Consistent with the substitution hypothesis, since turnover peaked in early 2022, there has been an increase in “internal mobility” discourse. For instance, of the 49 results on Harvard Business Review’s website for that term, almost half date from 2023 onward. Talent expert Josh Bersin published his Internal Hiring Factbook in 2023; my former colleagues at LinkedIn regularly produce a Workforce Learning Report.

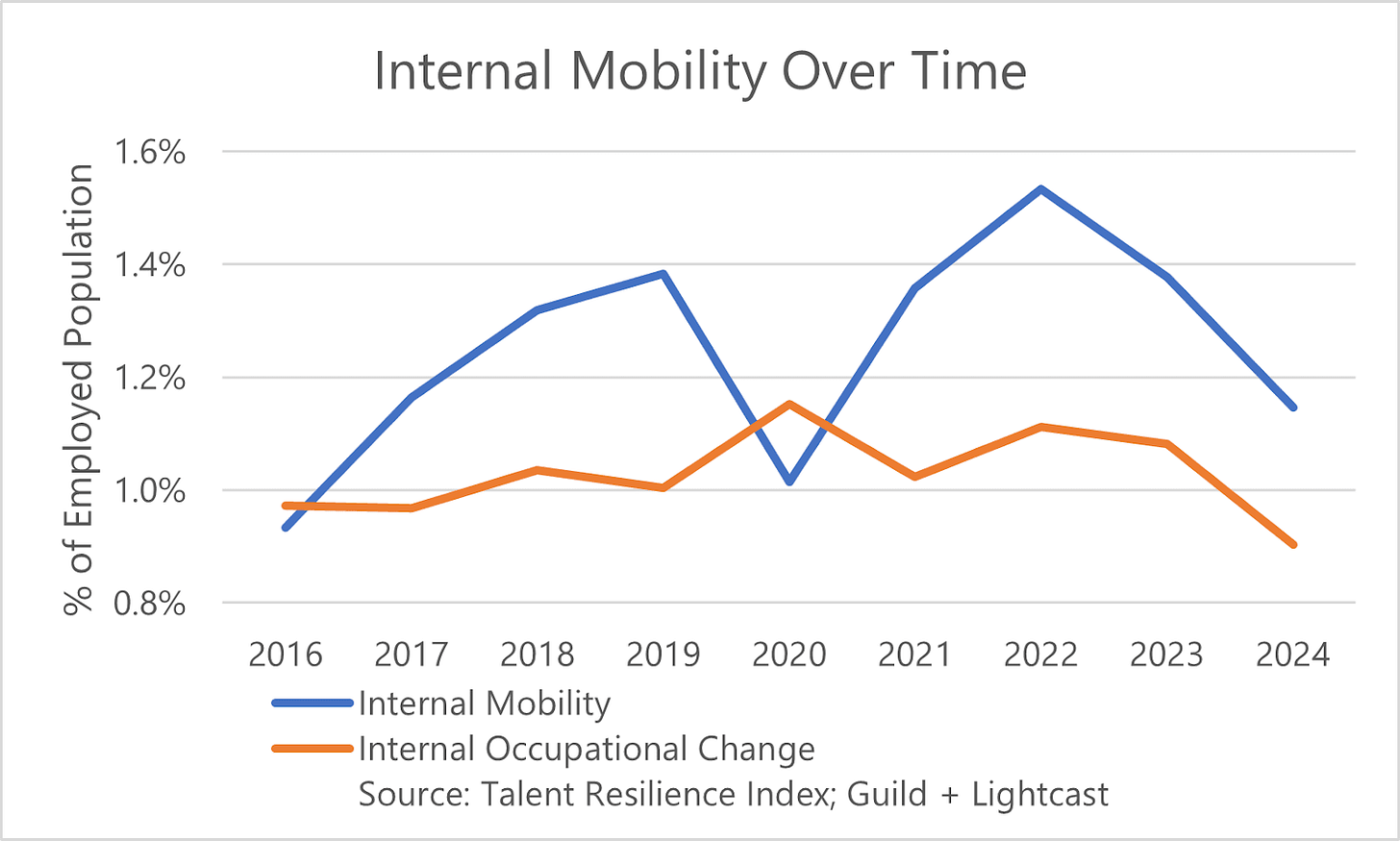

But as data from the Talent Resilience Index report indicates, that discourse has not been matched by an actual increase in internal mobility. The share of workers experiencing internal mobility exhibits the same procyclical behavior as turnover. Internal mobility, defined as any movement of talent within a company, either laterally or upward, rose from early 2016 to early 2022 before taking a sharp turn downward, and has fallen just below 2017 levels. A more stringent definition of internal mobility, limited to people who changed occupations within their firm, which likely requires a more deliberate reskilling effort, was lower in 2024 than at any point since at least 2016.

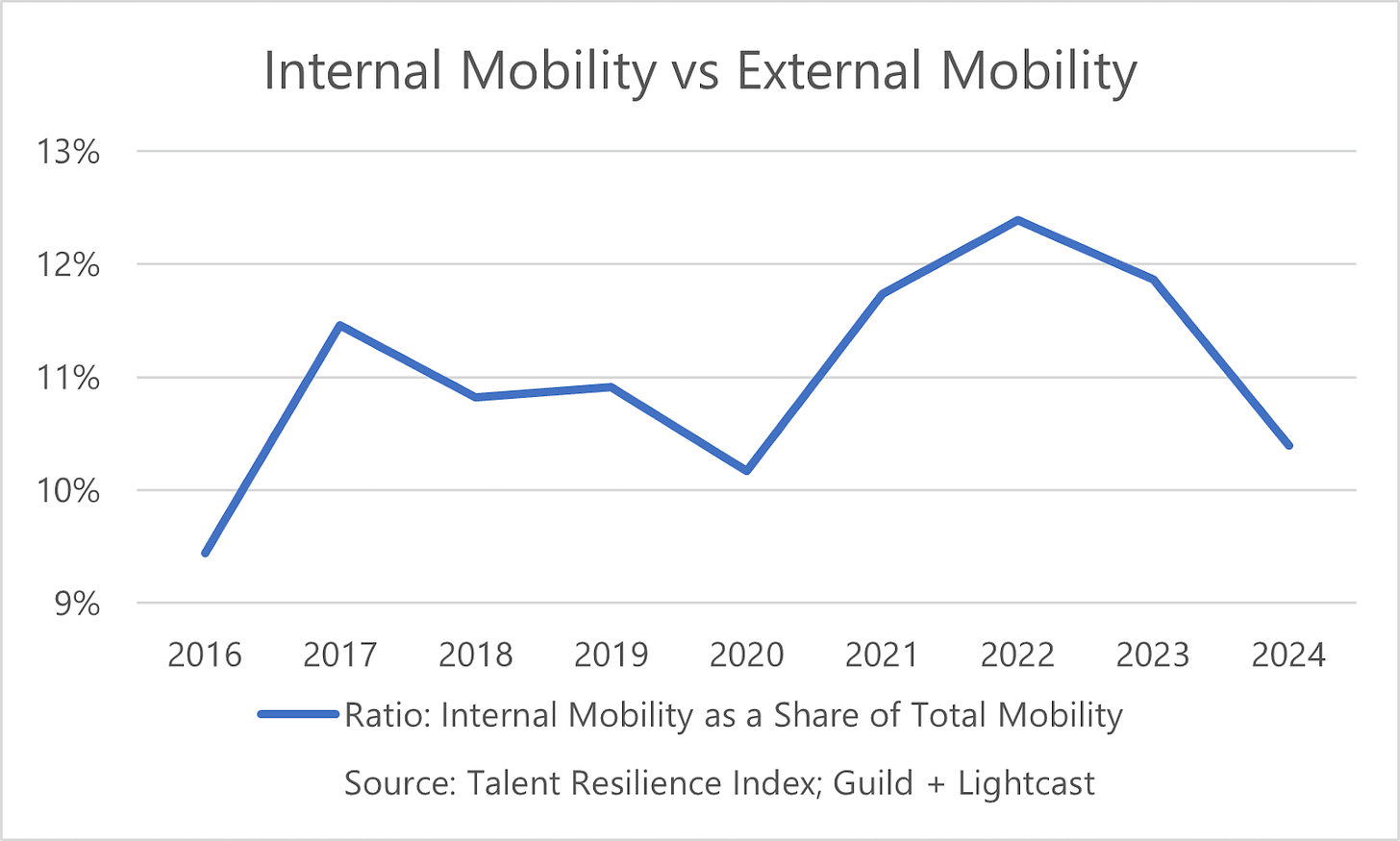

In fact, there’s some evidence in the TRI data that the relative reliance on internal vs. external mobility is pro-cyclical. When labor markets are really hot, internal mobility ramps up more than external mobility; and when labor markets cool off, internal mobility falls more than external mobility. In other words, while the US labor market is experiencing less of both mobility types than it did during the peak of the “Great Resignation” (2022), internal mobility has receded even more than external mobility.

What Should We Make Of This?

So despite being theoretical substitutes, turnover and internal mobility have acted like complements in practice. This isn’t my area of expertise (if you’re reading this and are an expert, please chime in!), but I have some ideas for why this happens.

The first is a pretty basic observation: in boom times, companies have an expansion mindset. This creates opportunities for people, whether they come from the inside or outside. When times are tougher, opportunities in a company are typically scarce - both for existing employees and potential hires.

The second is the pool of potential external hires, which gets much deeper when times are bad even as the internal talent pool remains the same. External candidates that were unattainable in 2022 have become much more available in 2024. This probably helps explain why internal mobility has fallen more sharply than external mobility during “The Great Stay”.

The third is that the cost-cutting exercises that are typically associated with periods of low hiring also impact resources for retraining of existing employees. This throws more sand in the gears of internal mobility.

Fourth, it may be that the same factors which cause procyclical behavior in employers’ quitting decisions (how many opportunities exist outside; the risks of taking a new role) also affect their internal mobility decisions. Folks talk of “job hugging” in the context - perhaps employees hug their old jobs and teams rather than rolling the dice with new ones, even at the same company.

Finally, tracking mobility within firms is much harder than across them, even with high quality profile data, so I’m crossing my fingers for similar analyses in the future.

What Can Employers Do About This?

I’m an economist, not a workforce strategist, so take these recommendations with a grain of salt. But let’s start with: companies should be honest with themselves and their employees. Promises about internal mobility are cheap, but in real life, many firms are reluctant or unable to actually implement it. They turn to internal mobility only when talent is scarce. At that point, they need to expand the pool of potential candidates - and that’s when they finally take a look at their own employees.

Yet when the market cools, some employers engage in penny-wise, pound-foolish decisions, including pulling back on investment in retraining their workers as a cost-cutting tactic. It is possible that this seemingly short-term lever-pull will make it particularly difficult to enable internal occupation changes as the skills needed to be successful evolve.

One of the explanations offered for why employers have been reluctant to lay employees off during “The Great Stay” is regret for being too quick to shed (and then rehire) talent after the COVID recession. It may be that cutting investment in retraining their workers as a cost-cutting tactic is a similar short-termist mistake, and will make it particularly difficult to enable internal occupation changes as the skills needed to be successful evolve. It’s important that leaders dig deeper into the data to understand the risks and opportunities here, and don’t just hone in on one figure that supports their short-term needs.

Finally, to the degree that job hugging is the problem - employees avoiding a new internal opportunity because they think it’s risky - employers can provide more institutional insurance. A potential internal hire will be more likely to take the leap to an organization with a perceived safety net created by a culture that invests in their teams.

A Final Thought: labor markets go through cycles. We’ve been in a slump for a few years and the slump could continue for a few more. But at some point in the future, talent scarcity will return and actual internal mobility (not just talking about it) will return to vogue. Companies that figure out how to do it properly, and not just performatively, will be one step ahead.