Can't Turn Back the Hands of Time

Addressing a Labor Force Participation Misconception

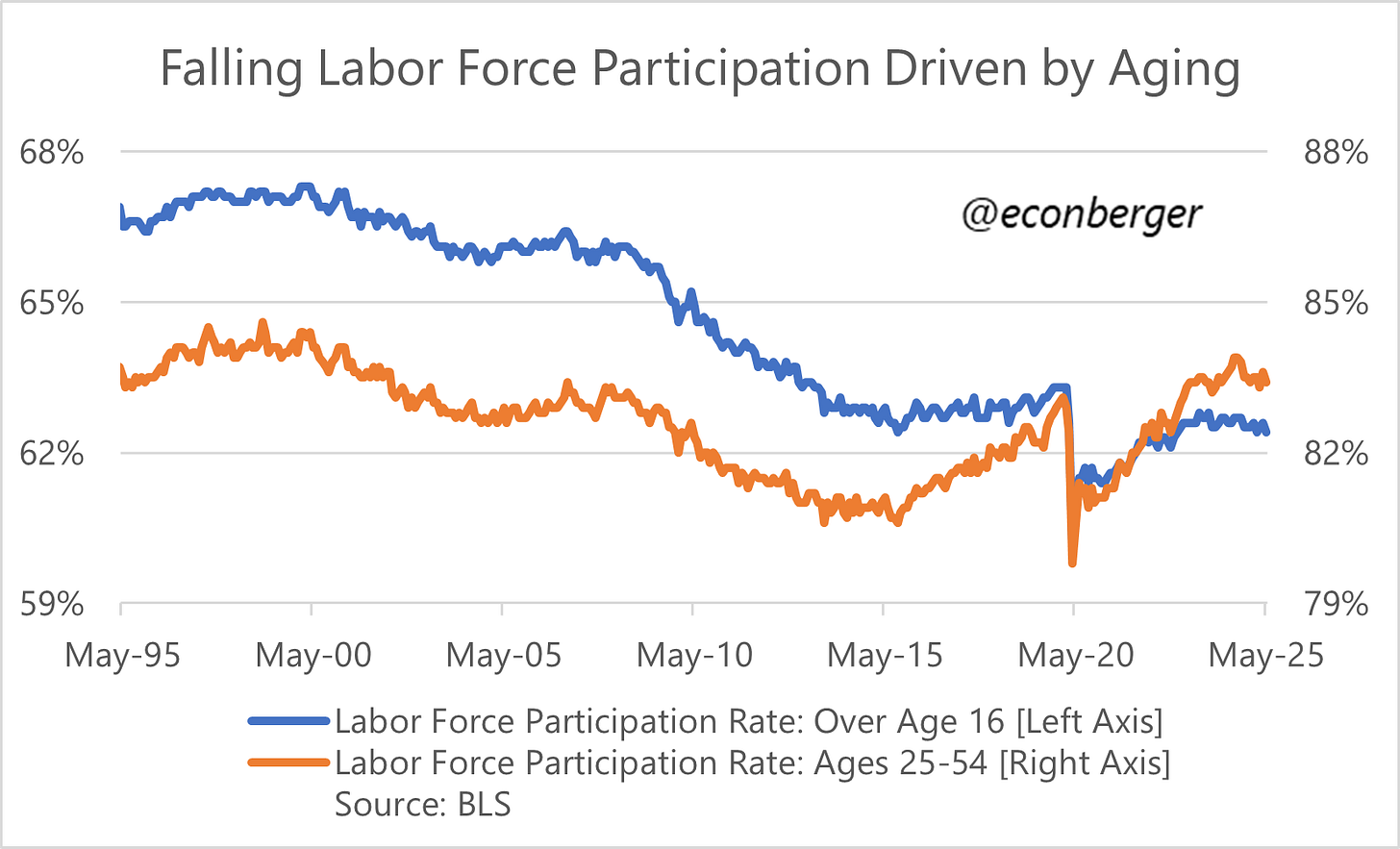

TL;DR: Labor force participation has fallen because the US population is getting older and its decline is not an indicator of an unemployment rate “undercount”.

More below chart.

The unemployment rate is an extremely useful labor market barometer, but it isn’t perfect. It doesn’t include marginally attached workers (people who would probably take a job if it was available but aren’t actively looking for one) or people who work part-time for economic reasons (those who have a job but wish they could get more hours/pay). And it probably understates how difficult it is to find a job right now.

That said, there’s a common refrain out there that goes something like “if the labor force participation rate were to return to its pre-pandemic level, the unemployment rate would be closer to 4.5%.” The implicit argument is that there’s a growing nugget of undercounted labor market distress relative to 5-6 years.

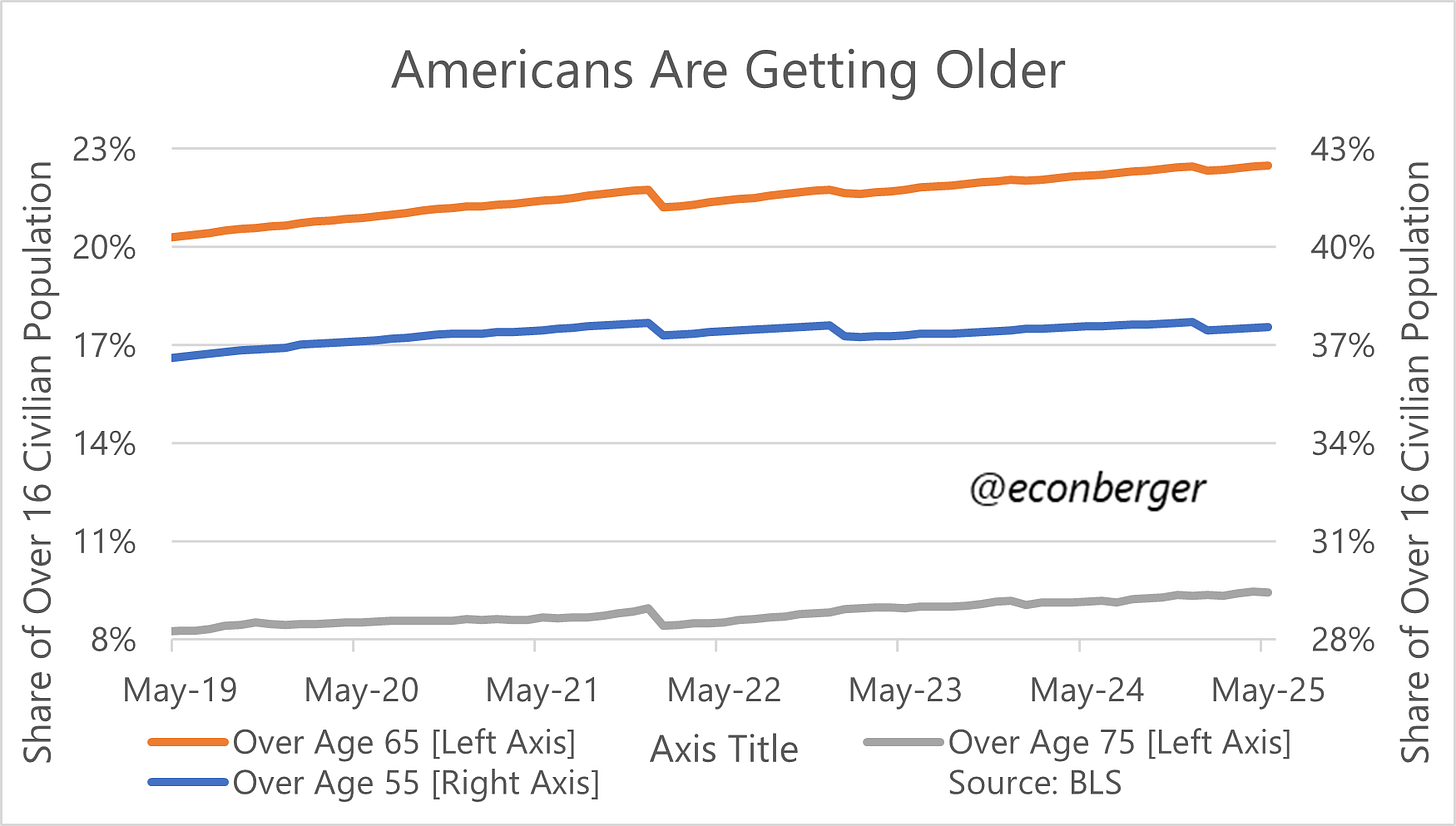

That argument is wrong. The main reason behind the falling labor force participation rate is that our population is getting older. Depending on how you define “older”, their share of the population has gone up by 1-2 percentage points. Older age groups tend have lower participation rates than the population average (due to retirement). So just mechanically, participation rates are going to structurally decline over time, even if participation rates stayed constant within each age group.

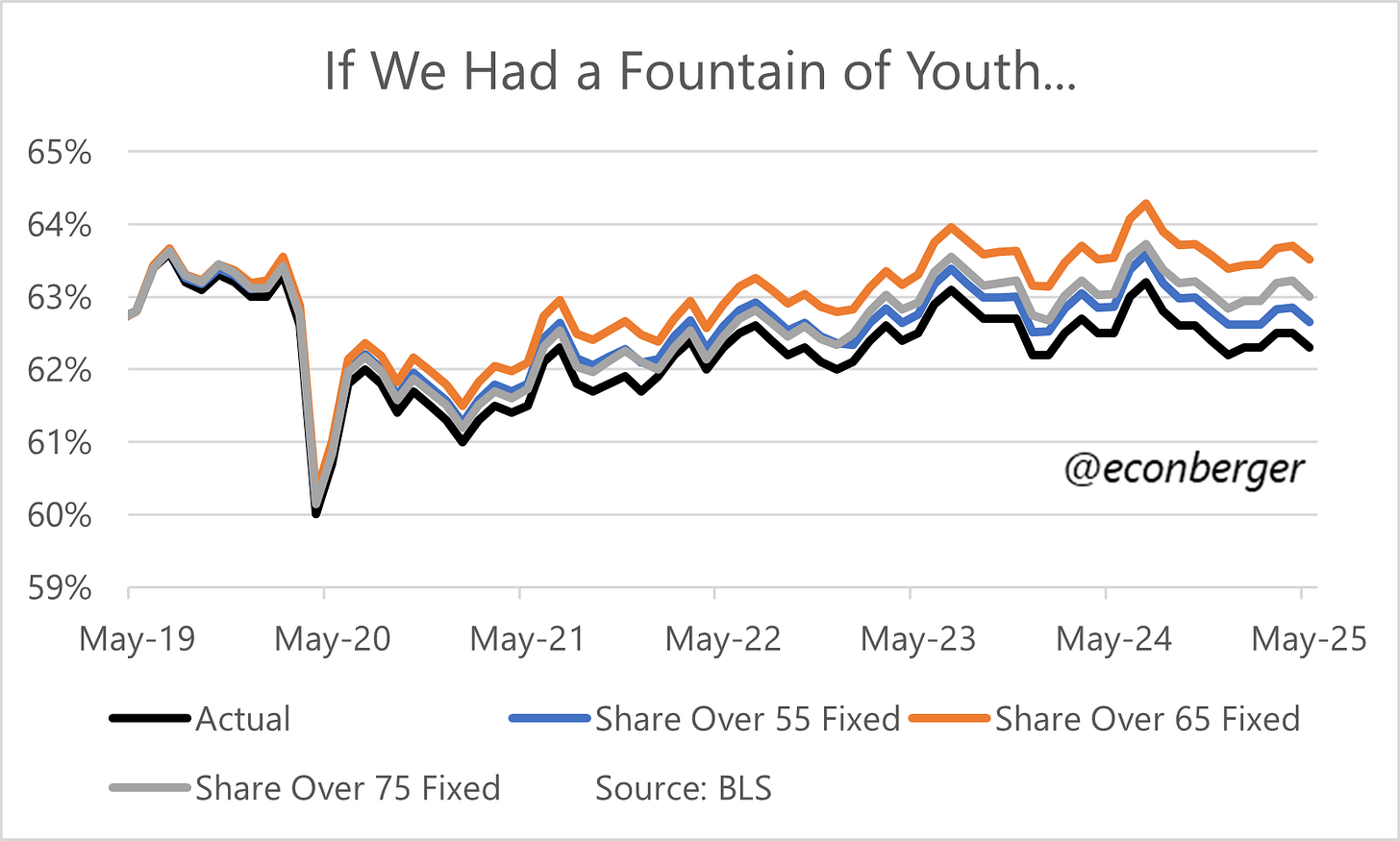

There are more sophisticated/complete ways of showing this, but here’s a simple and useful now. Imagine that we froze the share of the population over X age at where it was 6 years ago. That alone would wipe out some or all of the post-May-2019 decline in the participation rate.

The key takeaway is the labor force participation rate, while a useful indicator, is affected by both cyclical and structural forces. Both are interesting and worth thinking about, but if you’re talking about “labor market strength”, the cyclical forces are the ones that matter… and you need to control for the structural ones. A very good shorthand is the prime working age participation rate, though there are even more sophisticated approaches out there.

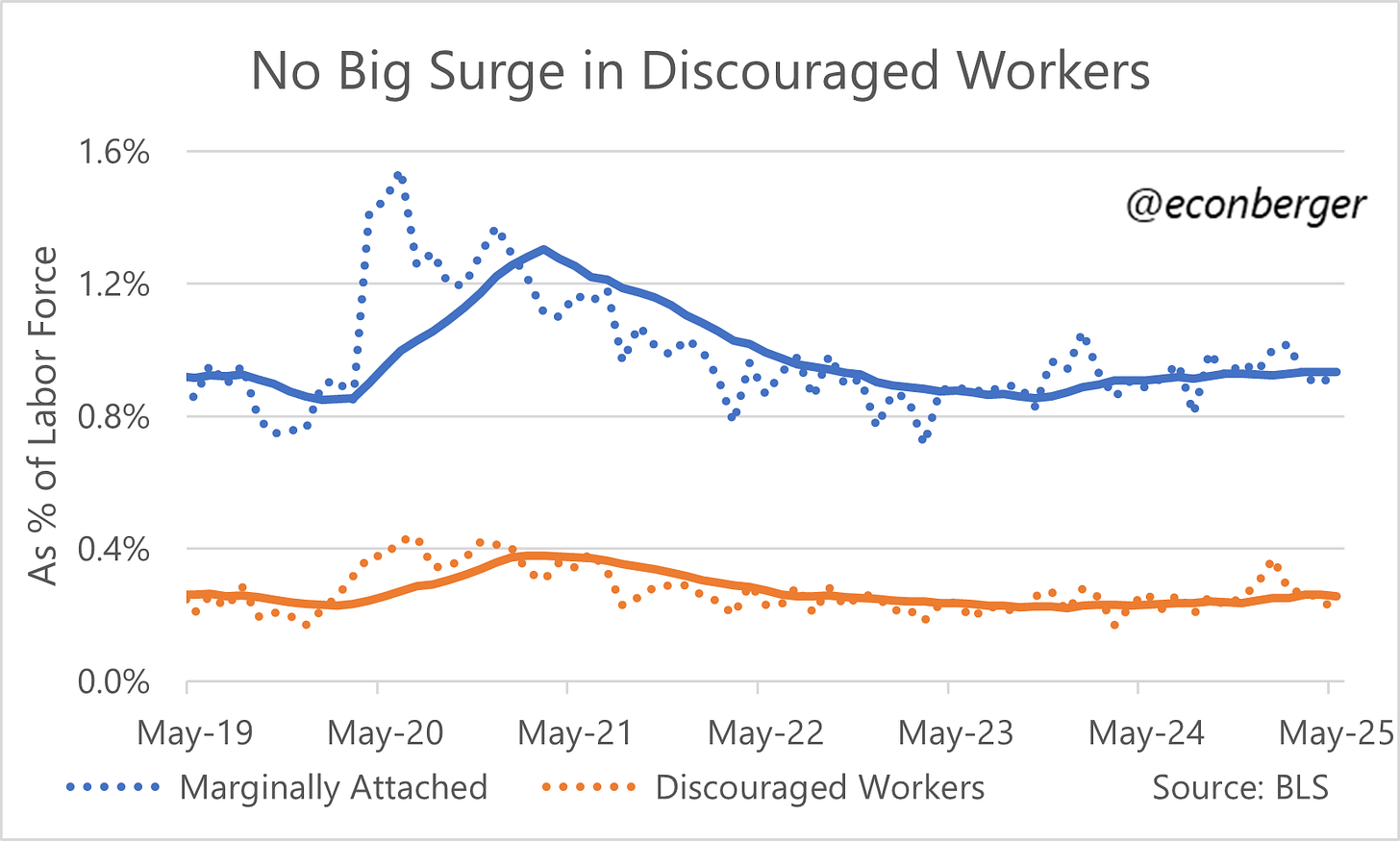

A final point: the BLS does try to track labor market distress outside of unemployment. For instance, it publishes a series called “marginally attached” which counts people who are not actively searching for work (neither employed nor unemployed) but have searched for work in the prior year. And within that group, it also tallies up “discouraged workers” (folks who are marginally attached, and say they aren’t currently looking for work because they believe none is available).

Both of these series are up a little over the past year or two, but remain at roughly the same levels as pre-pandemic. Neither indicates a meaningful increase in “shadow unemployment”.