TL;DR: After a run of very robust jobs report, April’s BLS data was merely decent.

Key Data Points:

Unemployment rate: rose to 3.9% (eh)

Prime working age employment population ratio: rose at 80.8% (good)

Nonfarm payroll employment: rose by 175K (solid)

Wage growth: ~2.6-2.8% annualized over the past 3 months (great from the Fed’s perspective)

Topics I’ll cover in this recap:

The Big Picture

Wage Growth

Miscellaneous

1. The Big Picture

We got really spoiled in the last few months - nonfarm payroll gains increased by 269,000 per month in the first quarter, the best 3-month stretch since last spring. With such elevated expectations, it was inevitable that April’s 175,000 increase (a solid number by the standards of the past 15 years) would underwhelm.

And while the “job gains are reaccelerating” hypothesis that briefly gained traction has gone back into hibernation, the “job gains have stopped decelerating” hypothesis remains comfortable intact. The 3-month moving average, now down to a robust 242K per month, is almost identical to what it was a year ago (237K per month).

What has changed in the past year is stronger labor supply growth; we have the same pace of job gains but it isn’t having the same impact on labor market “heat” as before. The unemployment rate is up a little bit over the past year, as are the shares of the labor force who are working part time for economic reasons or unemployed due to permanent layoffs. Coupled with the softening JOLTS hiring and quits data as well as renewed moderation in wage growth (see below), this really is a cooler job market than a year ago.

That said, it’s murky whether cooling is past or present tense, and also possible that some segments are reheating even as others chill further (which would be very normal near an aggregate steady state). On the reheating front, one of the best barometers on the report is the share of prime-working-age Americans with a job, which has been rising recently and is just shy of its post-2001 high.

To wrap up this section: 175,000 is not a bad or soft number. It maybe isn’t as good as it would be in times of weaker labor supply growth, but doesn’t warrant pessimism.

2. Wage Growth

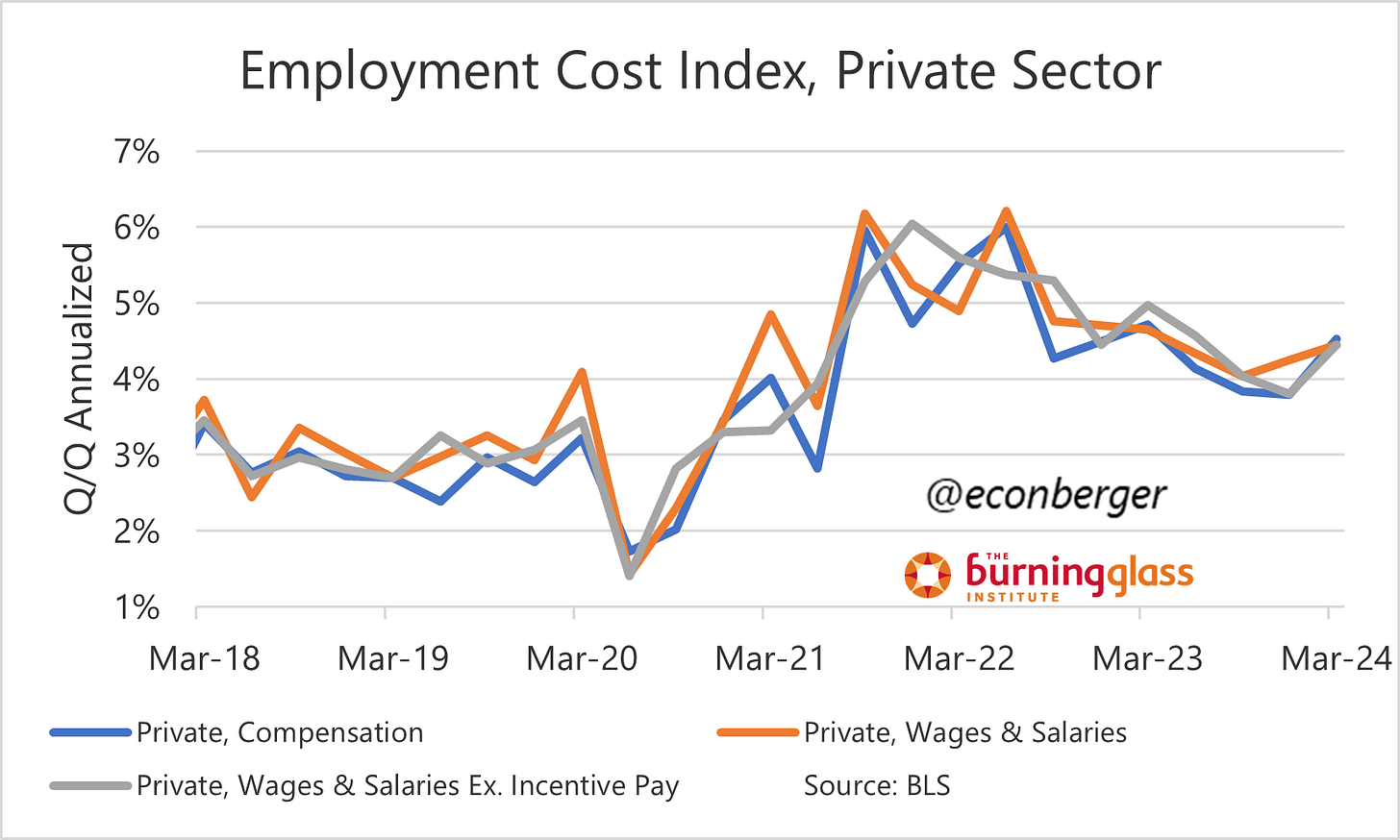

Evidence suggests that the causal linkage from wage growth to inflation is not that strong. But the Fed has repeatedly told us that they want to see wage growth come down (most recently at Wednesday’s press conference by Chair Powell). The employment cost index (ECI) data through March, our gold standard metric for measuring wages and compensation costs, refused to comply earlier this week:

Friday’s average hourly earnings data, which isn’t quite as good as the ECI but benefits from greater timeliness, looked a lot better in April (and may presage a future improvement in ECI). The annualized growth rate of 2.6-2.8% annualized over the past 3 months is comparable to what we experienced before the pandemic; if it sticks, and if you think wage growth plays a big role in driving inflation, then we’re headed for some good inflation data.

Of course, if like me you’re a skeptic about the wages/inflation linkage, this doesn’t tell us much about future inflation. It matters a heck of a lot that we see genuine and very significant improvement from the actual consumer price data during the remainder of the year; some improvement is likely, but will it be enough to get the Fed to ease this year? The bar to reaching the Fed’s March forecast is set quite high.

3. Miscellaneous

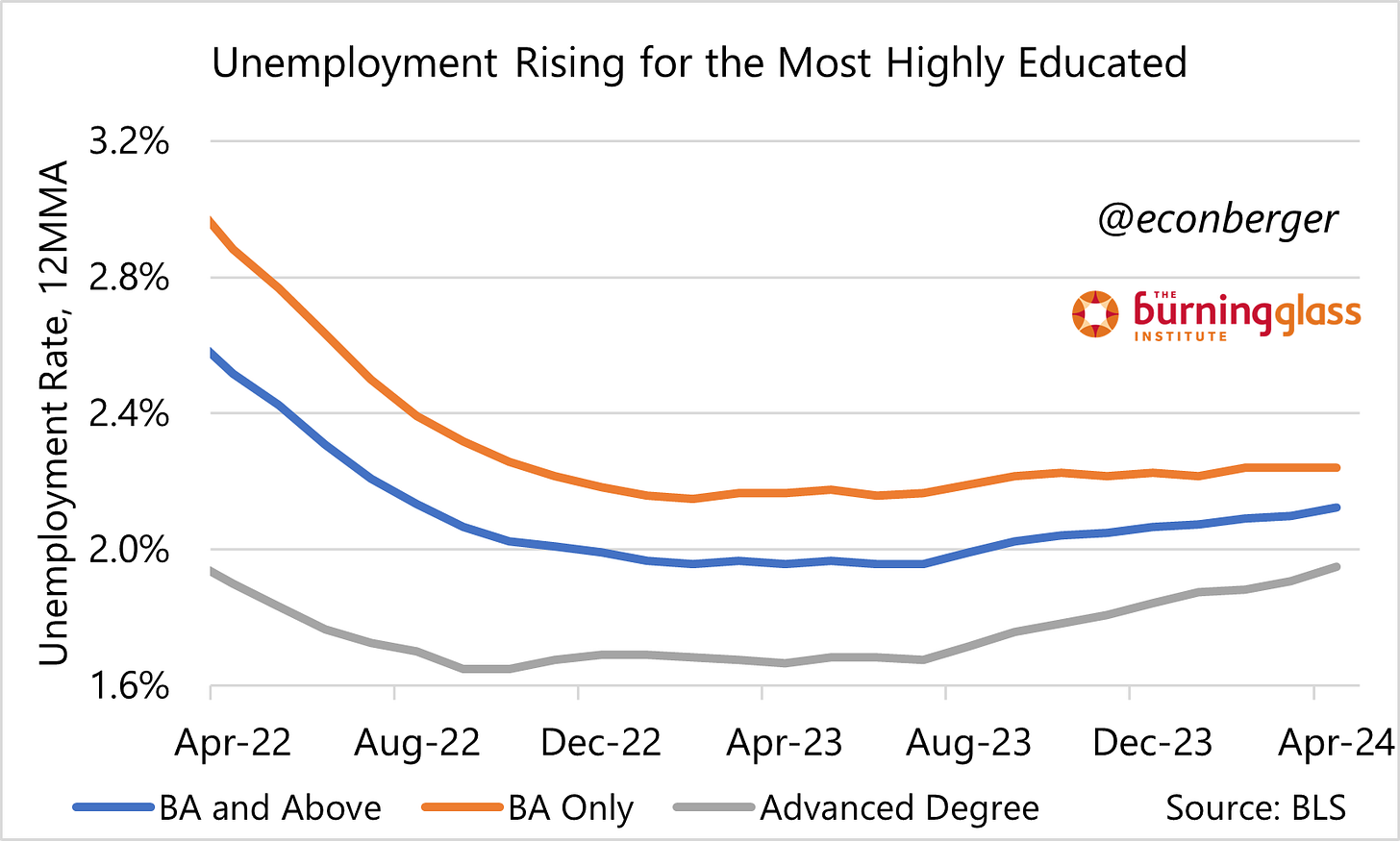

If you read this newsletter, you know I have a few hobbyhorses. One is the slump in the labor market for people with advanced degrees, even as the labor market for “BA but no more degrees” continues to coast along. The gap between these two segments hasn’t been this narrow since early 2019, and back then both segments were moving in the right direction. (I talked to Business Insider’s Aki Ito about this in a recently published article.)

Another hobbyhorse is how, while the immigration-driven surge in labor supply is cooling the overall labor market, it’s having a very minor to non-existent impact on the labor market for native-born Americans. The unemployment rate for foreign-born Americans is higher than that for native-born Americans for the first time in more than 2 years. To recall an earlier point, in a mildly cooler labor market, some segments have chilled much more than others.

See you next month!